Waswo X Waswo talks about his karkhana and life in times of quarantine in Udaipur, Rajasthan, in an interview with Sonalee Tomar for Asian Curator.

My Evil O YouTube channel had already been around for one year when this lockdown began, so it was well positioned to quickly attract viewership to its Sunday “Coronavirus Artpocalypse” series, and the recently started Wednesday “Dialogues”.

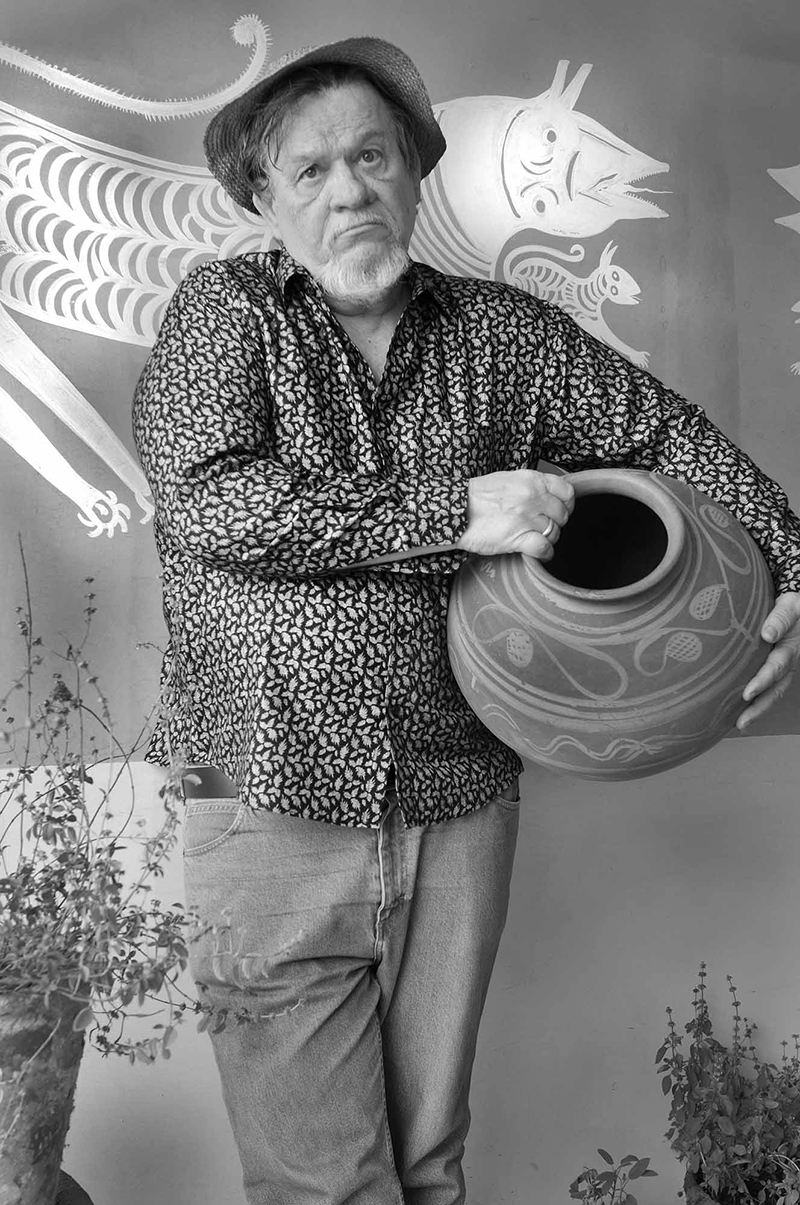

Waswo X Waswo.

AC: Tell us about your own personal evolution, vis a vis the beginning of your journey with photography to the (collaborative) work that you do today.

To this day I never see my work as individual statements, but rather, portions of a much larger tale.

WXW: In college I actually studied literature and creative writing. My dream was to become an author. The switch to art was only later, in my mid-twenties. I did come from a very arty family. My mother painted traditional American landscapes, my dad painted flowers, a distant cousin taught art in public school, and her husband was the Art Director at the local natural history museum. So there was precedent for me choosing the career, and quite a bit of family encouragement. I began with wild painted abstractions, which were still in vogue, and later discovered photography.

Photography began to become all-consuming, and I studied it for several years, both in my home town and later in Italy. I spent countless hours in the darkroom. My training was in making fine chemical-process black and white silver gelatin prints. I found myself drawn toward Pictorialism as a movement. It was very out of fashion, but I had a love for vintage-style aesthetics. Soon I discovered that my love for story-telling was very much alive. The individual photographs that I made began to tell a story. To this day I never see my work as individual statements, but rather, portions of a much larger tale.

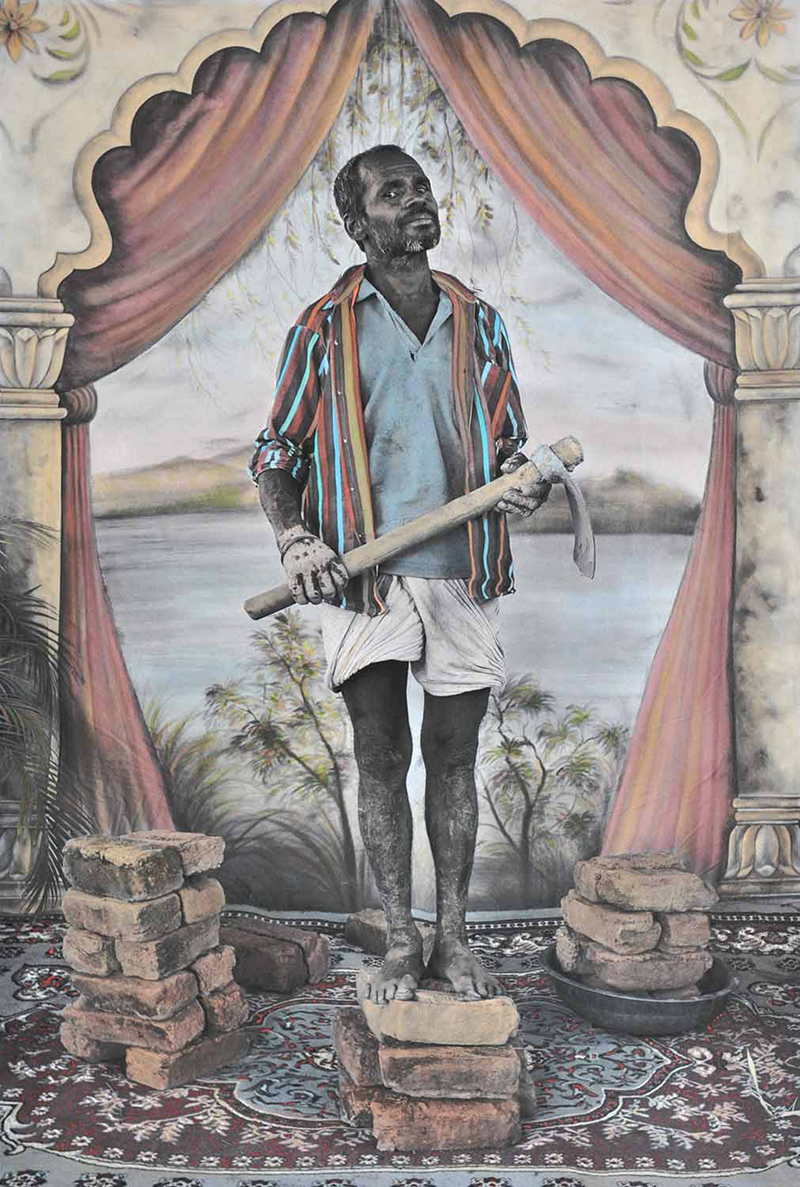

Kashu on a Brick Pedestal. 2018.

AC: How do you deal with the conceptual difficulty and uncertainty of creating new work?

WXW: When I first started to widely exhibit in India, back in 2001, I found myself becoming quite reactive to frequent criticisms that my photographs were “Orientalist”. In retrospect I better understand those criticisms. In those days the preferred narrative was that India, like China, was the rising new superpower, rapidly modernising and gaining in both wealth and influence, and here was I, exhibiting sepia-toned photographs of rural landscapes and portraits of villagers in traditional dress. Throughout my career I had eschewed the encroachment of what I saw as signs of globalisation in my art. People called it nostalgic, but I had a deep love of simpler and quieter places and peoples, who held onto a sense of cultural roots. I had done the same sort of photography in Italy.

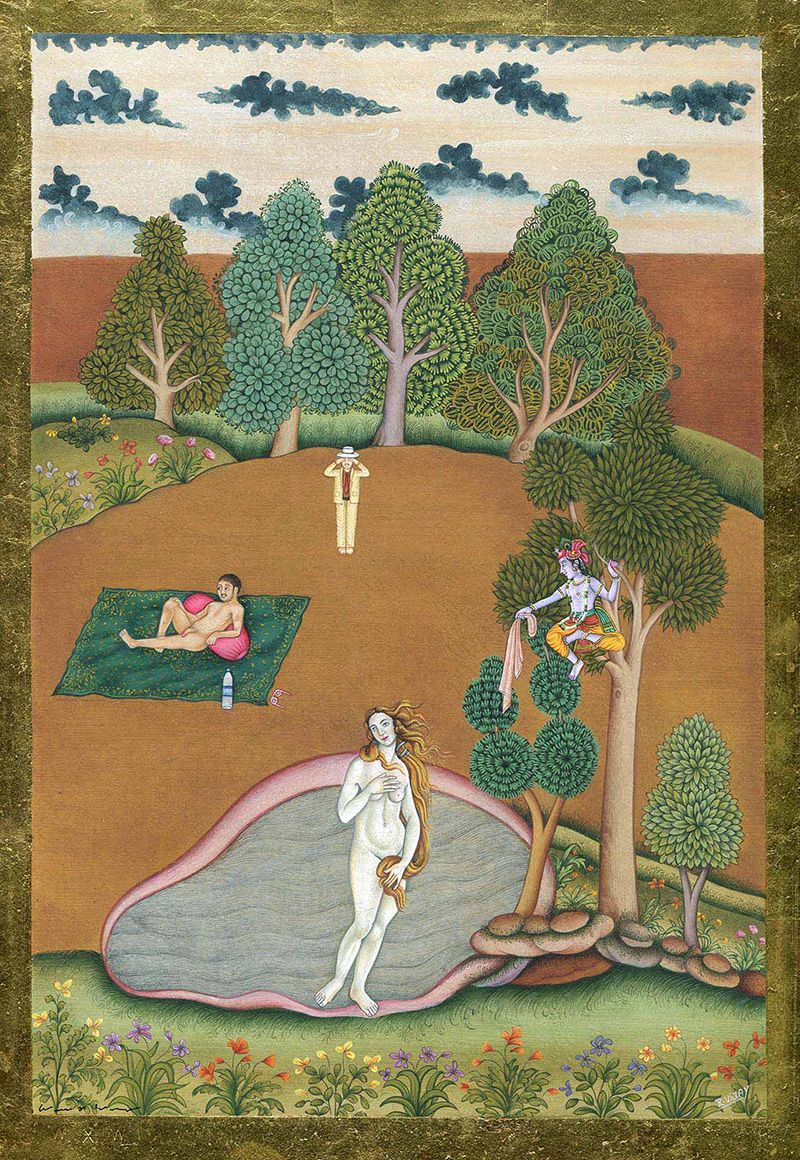

The miniature paintings began to look at me, the outsider, something that my photographs could never do, whereas the new hand-coloured photographs carried on the vintage feel of my older sepia prints, but added a healthy dose of playfulness, self-awareness and contemporaneity.

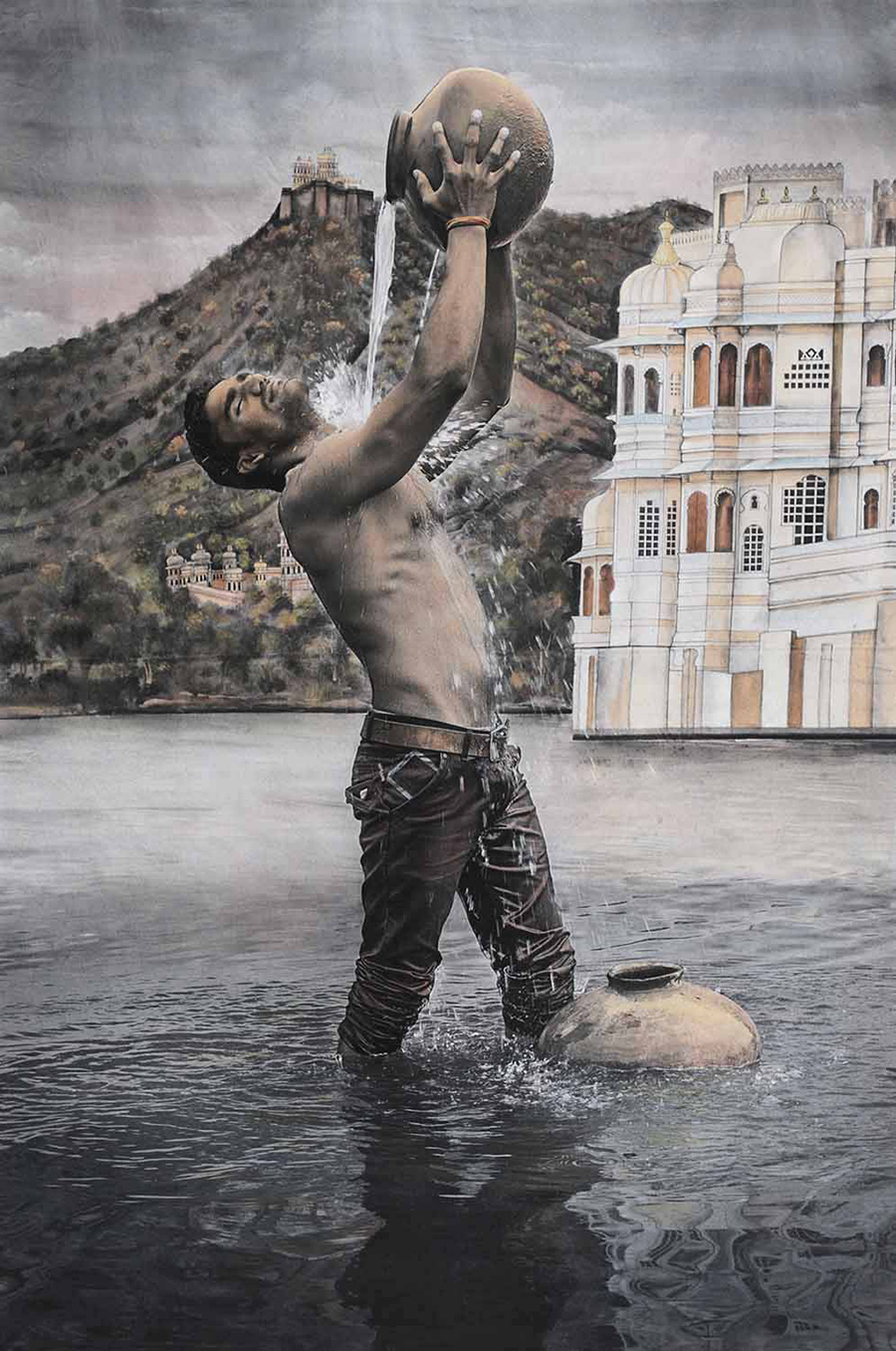

Of course between 2001 and 2004 that approach did not gain favour in India. By 2006 I had settled in Udaipur, Rajasthan, and made a major conceptual shift in the way I approached my art making. I began to use photo backdrops painted by teams of local artists, and, more significantly, partnered with Rajesh Soni, the by now quite famous third generation photo-hand-colourist who is the grandson of Prabhu Lal Soni, the court photographer to the Maharana Bhupal Singh of Mewar. At nearly the same time I partnered with R. Vijay, a local miniaturist who was a grand-nephew of Indian artist Ramgopal Vijayvargiya. By collaborating with these two, the narratives in my work expanded. The miniature paintings began to look at me, the outsider, something that my photographs could never do, whereas the new hand-coloured photographs carried on the vintage feel of my older sepia prints, but added a healthy dose of playfulness, self-awareness and contemporaneity. My move to Udaipur, and the new collaborative way of making, started to gain favourable notice.

In 2008 we had a breakthrough show simply called “A Studio in Rajasthan“. The show travelled between the old Mattancherry space of Kashi Art Gallery in Kerala, and Palette Art Gallery in New Delhi. Suddenly we were on the India art map in a rather positive way. This long growth of experience has caused me to carefully think through new concepts, but in the end I still go by my gut feeling. I’m very visual in the way I approach art. If I conceive something in my mind that I think strongly speaks to me, I will surely go with it.

Blue Series 9

AC: What were you working on when the lockdown was announced?

Last year we had an extremely successful show of the miniatures at Gallery Espace in New Delhi. That show was a year and a half in the making. It contained over fifty miniature works, plus for the first time a few marble sculptures. It was a very complex show: difficult to organise conceptually and supervise the paining (R. Vijay and I had brought in two assistant painters), plus I was doing a few marble sculptures for the first time. Since I had very little time to utilise my Udaipur photo studio in 2019, I had planned that 2020 would be a big return to photography. I had asked my co-worker Dalpat Singh to organise his painter team to produce new backdrops.

Sometimes we need to wake up in the middle of the night just to evade the lockdown so that we can physically exchange wasli paper and finished paintings.

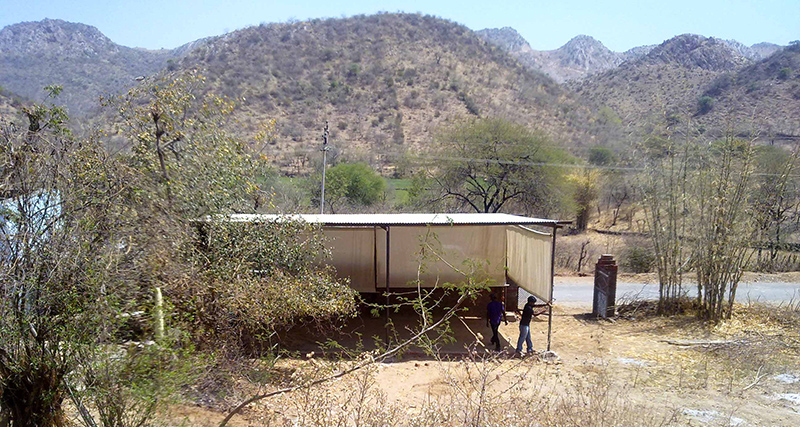

When the Covid-19 crisis first struck I was hoping that we would still be able to make it out to the studio, which is in the Village of Varda, about a thirty minute drive from my apartment. But sooner than anyone imagined, we were all locked down in our houses. Thankfully, R. Vijay, Dalpat, and our longtime border painter Shankar Kumawat are all able to continue work from their homes. We communicate via WhatsApp image transfer and mobile calls. Sometimes we need to wake up in the middle of the night just to evade the lockdown so that we can physically exchange wasli paper and finished paintings. But work goes on.

The Varda Photo Studio

More and more I call my extended team the “karkhana”, which of course means “factory”, but has a much older meaning as a miniature painting atelier. There would always be the master artist, the assistants, the border painter, and younger apprentices who would be kept busy grinding pigments. I’ve come to like this word karkhana, and in fact hope that my next book will be titled the same.

AC: How has this affected your practice and plans?

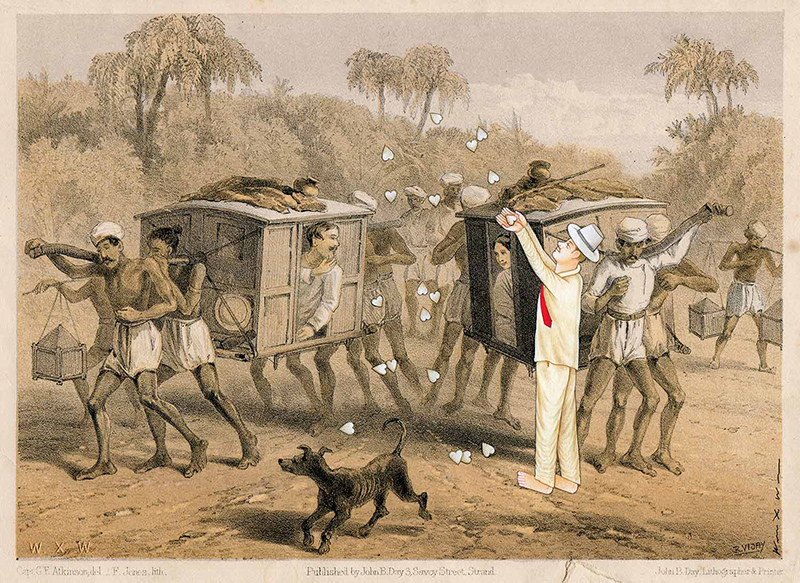

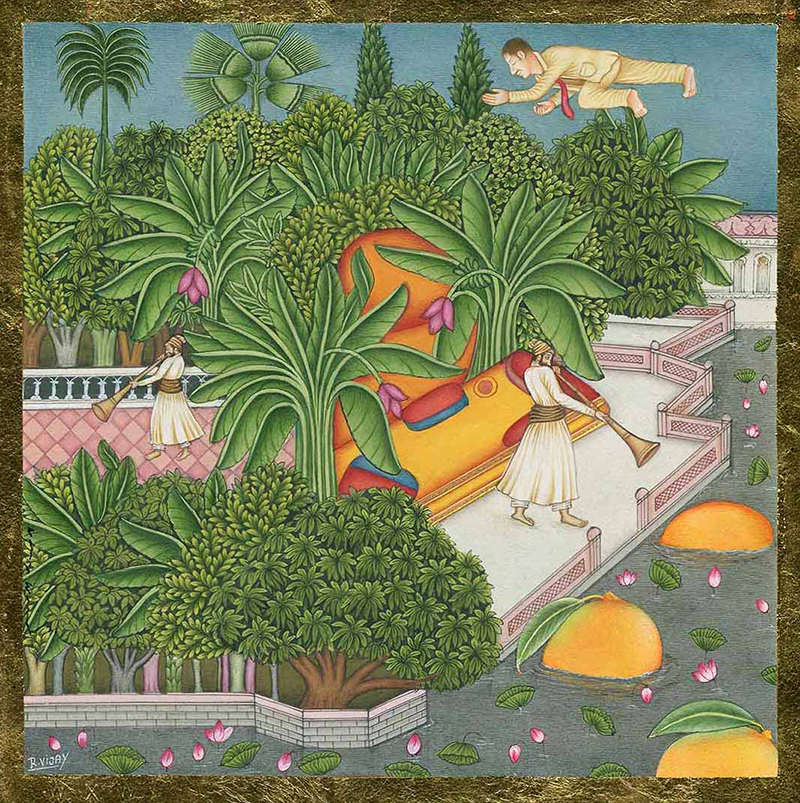

More and more I call my extended team the “karkhana”, which of course means “factory”, but has a much older meaning as a miniature painting atelier. There would always be the master artist, the assistants, the border painter, and younger apprentices who would be kept busy grinding pigments. I’ve come to like this word karkhana, and in fact hope that my next book will be titled the same. Working in the manner of a karkhana system, we often keep several projects running concurrently. So right now R. Vijay is completing a large master work in which the border has already been completed by Shankar Kumawat, and later it will receive some gold edges done by another artist. Rakesh (R. Vijay) is also taking some breaks from this large painting to continue work on a new series of ours titled “The Intruder”, in which our usual figure of the fedora man is being ironically inserted into vintage Curry and Rice lithographs by George Franklin Atkinson.

Meanwhile, Dalpat continues to prepare photo backdrops, as well as paint some background work for future miniatures that Rakesh will finish. I’ve helped Shankar move away from only border work, so he is now exploring some new directions under my guidance. Rajesh Soni finds himself with little hand-colouring work right now, but he is so entrepreneurial I do not worry about him. He’s mostly using this time to make photo-documentary images, as he has his own press pass. I’m very proud of this entire team. As for myself, I’ve been busy with working on the next book, my Evil O video channel, as well as the usual mandatory networking. The motto of our karkhana is “We Are Always Working”, and we actually try to do that, so the lockdown has only changed our methods.

The Intruder.

AC: What would elevate artists’ life during this period?

WXW: I have sometimes broken down weeping during this first five weeks of this lockdown. The loneliness of being on my own, deprived of freedom, is sometimes overwhelming. But the team does its best to keep up my spirits. I’d say the best thing any artist can do is just keep working. Boredom and loneliness only exist when you become idle. Organise your portfolios, sort your files, email galleries, sit down and write out new projects, create layouts and mockups in Photoshop, draw, sketch, paint, sing, poem…these things will help you stay sane.

Self Portrait in Lockdown.

AC: What kind of critical inputs does the art world need at this moment to overcome the loss of income and opportunity as a direct result of the lock-downs worldwide?

WXW: I’m afraid that I’m not optimistic. Even with the best of luck, it seems to me that we are looking toward at least one year before we begin to come out of this and return to some semblance of normality. Small galleries will be hurt, and large ones will struggle. Artists who have no other income to fall back on will be in dire straits. The best we can do is hold together the community, the interest, the passion and the histories of what is now our contemporary art heritage. Already I’ve noticed a large uptick in galleries going online to organise symposiums and interactive talks, and virtual walkthroughs of virtual exhibitions. It is a time we need to be extraordinarily creative.

My Evil O YouTube channel had already been around for one year when this lockdown began, so it was well positioned to quickly attract viewership to its Sunday “Coronavirus Artpocalypse” series, and the recently started Wednesday “Dialogues”. We also must not forget the need for books, journals, and diaries, and this is a perfect time for writing. It’s the moment we must piece together the recent past, archive, interview, discuss, bring new talent to light and plan for a future we desperately need to keep faith in.

In The Garden of Archetypes.

AC: How does your interaction with a curator or gallery evolve?

WXW: I’m pretty old-fashioned in my dealings with curators. The art I make with the karkhana is very personal to me, and part of a very long narrative that spans my experiences and emotions living as a foreigner in India. Too many times I’m asked to make work on one theme or another for particular shows, and unless I deeply feel the theme fits with a direction that we’re already going, I decline. There’s also the problem that many curators have come to assume that contemporary artists can make works to order very quickly, whereas the skill level and patience and time that goes into our works largely prohibits short-notice deadlines. We prefer to work with curators who have some knowledge of our working methods, and a respect for what is being said via the art. If that fits their theme, then we are always prepared to enter an exhibition.

Shooting at Badi Lake in Udaipur.

AC: How do your audience and the market interact and react to your work.

WXW: Well, I’ve quite a few books to my name now, the latest two being “Photowallah” that was put out by “Tasveer“, and last year’s “Gauri Dancers” published by Mapin. Gallery Espace keeps making good sales for us, with recent participation in Art Basel Hong Kong, and nearly every year at the India Art Fair. The exhibition last October, which was titled “Like a Leaf in Autumn” which primarily dealt with “whiteness” proved a huge success, with good reviews in reputable sources such as India Today, The Economic Times, and others.

2015 – A Monsoon Shower

AC: Tell us about your studio, what kind of place is it? Could you describe your usual work-day in the studio?

WXW: Due to the way I work, with a several collaborators, “going to the studio” is actually often a day of rounding. In normal times it might start with Ganpat and I driving the Jeep out to Varda, where we might make a photograph after arranging some backdrops and props, and then share a beedi (local hand-rolled cigarettes) with the landlord, Manohar Singh, while sipping chai brought by his wife. Then we might exchange the jeep for the Enfield, and navigate Udaipur’s narrow back alleys to Shankar’s house, where we sit and chat and check his progress on a miniature border or one of the new series. After that we might meet Rajesh for a coffee at our favourite coffeehouse at the lake’s edge, and talk about the upcoming photographs that need to be painted. Then it’s onward and up a small hill to Dalpat’s small workshop where we check and advise on a new background being painted, and finally, back into the Jeep for a long ride out to Rakesh’s studio to admire how he’s progressing on the new miniature. Oh how I love those days! This lockdown has stolen a huge piece of happiness from my heart. But we have to continue, however we can.

Dreams of the Orientalist. Waswo X Waswo.

AC: How are you balancing life and work at home during this period?

WXW: “We Are Always Working”, is our motto, but truth is that all of us in the karkhana take time to just live and relax and breath. I firmly believe that you cannot make art without an authentic story to tell. So for us, living life, enjoying its ups and suffering its downs, is probably the most important part of the creative process.

Before you go – you might like to browse our Artist Interviews. Interviews of artists and outliers on how to be an artist. Contemporary artists on the source of their creative inspiration.

Add Comment