Roshan Mishra, director and executive curator of the Taragaon Museum, Nepal treads a fine balance between preserving the ancient historicity of Nepal and being a steward of contemporary culture. The multi-hyphenate talks to Sonalee Tomar about the lofty visions of the future of art in Nepal – like a museum at the foothills of Mt. Everest.

“An exhibition should not look like a book on a wall and artist sometimes respond adversely to being corralled into a concept. You need to strike a balance, satisfy the audience, and earn the respect of an artist”

– At the back of my head, I always remember this quote by Nicolas Serota, when he was the director at Tate. I love this philosophy and given the size of our museum and gallery, this is a doable approach.

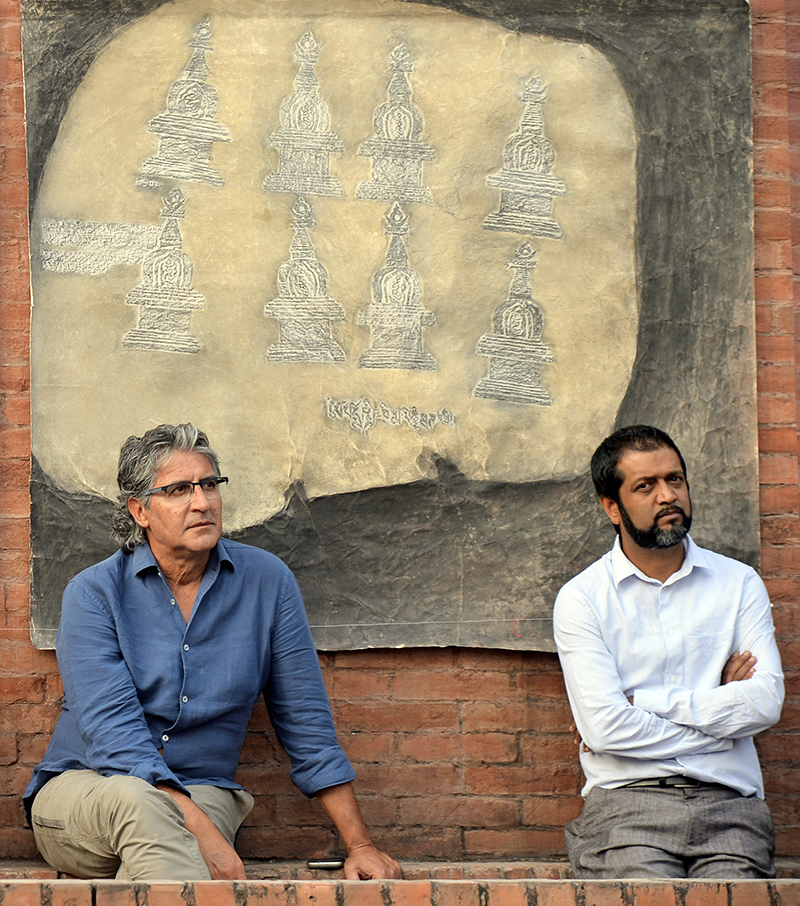

Exhibition – Taragaon Lecture series 7, 2019

Tell us about your role as Director of the Taragaon Museum.

My role is very diverse. One of my main tasks is to connect with scholars, who have lived and worked in this country, and introduce them to the museum’s mission and vision. This is important to us as most of our objects come as donations from scholars and individuals. Besides the management of the permanent collection, I am also highly engaged in our contemporary art gallery. As I am also an artist, I really enjoy getting involved with the contemporary art activities, this gallery is one of our busiest sections, as a space to promote Nepali art and the artist. The gallery displays the work of the senior, established and young upcoming artists on a regular basis. I also design and curate shows for this gallery. Besides this, I look after other projects from the Saraf Foundation for Himalayan traditions and culture. Nepal Architecture Archive (NAA) is an integral part of the foundation and the museum, and I manage and closely work with the archive and the library.

Taragaon Museum building architecture

How did your tryst with art begin?

I was born and brought up within an art environment; art and creativity were always surrounding me. I have seen my father painting and drawing all the time; I used to sit and paint with him. This obviously took me to arts college after finishing my school. I was influenced a lot by my father who was an eminent artist in Nepal. Even now when I paint, I see the colours coming from my father’s palette. After graduating from the Fine Arts College in Nepal, as many others, my wish was also to study abroad and that took me to London, where I further studied animation and digital art. After staying for almost 14 years in London and doing various jobs including graphics and interior designing; in 2013, I finally decided to leave London and come back to my home country Nepal. I had no plans about what I was going to do back in Nepal. I thought I would be staying in my studio and will be making works of art. When I came back, my thought didn’t work that way because of various different circumstances, therefore I started to look for a job. That was the same time when Taragaon Museum was looking for a Manager to run it. I went through the interview process and I was hired. That was the point when my career and my connection with art world was re-ignited again. If I was not back at that time, I would not have been doing anything that I am doing now. I would have been lost in London, and one thing for sure is that I would not have been working in a museum. When I look back now, I really feel that things happen for a reason. Leaving London at that moment was the right decision I made at the right time.

When I came back to Nepal, except my college friends, nobody really knew me. I was known a little because of my father but that was all. For 14 years, though I studied art and felt art was in my blood, my devotion in art kind of stayed dormant, as nothing much was happening. After joining the museum, things started to change. The passion and love for art that stayed dormant within me slowly started to kick in. Art has been always within me, it just needed a means to come out. Through the museum it came out in a different form. I was reconnected to the Nepali art scene, I was meeting young and senior artists, my circle was growing, PR was getting better and I was totally loving the new job, which gave me a pair of wings to fly and find my destiny.

Nepal Architecture Archive (NAA)

Nepal Architecture archive and Saraf Foundation for Himalayan Tradition and Culture. What were your motivations for moving from (specialised museum) Architecture to (more general and encompassing) Art?

Though I studied art, after joining the museum, I was more inclined towards the heritage, tradition and culture of Nepal, especially of Kathmandu valley. When I was suddenly exposed to these materials, being a Nepali, I realised that not only me but the whole generation of my age group and even the younger ones didn’t actually know much about our own tradition and culture. This realisation was another motivating factor that made me feel so connected with the archives. This interest eventually added multiple layers in my experience. This factor was very motivating because this was another dimension of art, which was completely unknown to me.

Later in 2016, the Nepal Architecture Archive (NAA) conceptualised and was announced by the Saraf Foundation, which is when I realised we were about to create something that didn’t exist before. Our foundation’s chairman Mr. Arun K. Saraf had a vision to bring back Nepal related materials made by foreigner scholars and individuals after 1950’s. In his own world, he calls it an effort of Gharwapashi (Bringing back home). This vision was also another motivational factor for me. This whole idea always stimulated me to work closely with the archive. I would not say that I moved from the specialised museum, but I would rather say that the museum and the archive complemented each other because I have not been able to talk about just the museum without mentioning the archive. They must grow in-parallel to have a bigger impact so that it can fulfil the vision and the mission of the foundation. We have also been involved in other collaborative documenting projects through the foundation. Nepal Heritage Documentation Project is another wonderful project that is documenting the heritage sites. In the last couple of years we have worked very hard to manage the archive and bring it to the current level; now our goal is to make it accessible to the public. Until now the archive has been accessible on request only.

Nepal Architecture Archive (NAA)

How does the audience react to your work?

I think this has been like a slow burning fire rather than a flame. The work that we are doing at Taragaon was slowly giving an impact in the Nepali art arena. There have been lots of coverage in the press in the past and our visitor count has also improved since the museum was opened to the public. We are not just a museum, there are so many other elements that make the museum complete. We have the permanent collection, contemporary art gallery, library, archive, open studio, café, multi-functional hall and other outreach programs and all this have fulfilled the demands of the audience.

What are you working on now?

At the moment, re-curation of the permanent collection is important to us, therefore we are all working with some of the galleries that we need to re-do and re-curate. Besides this, I will be mainly working with two programs I initiated last year for the contemporary art gallery. The first one is “Open Studio” which provides a working space within the museum for young artists. They will work for a month and we will host an exhibition of their work. Secondly, I initiated “Object in Focus” series, which is a curated single object exhibition. This allowed viewers and artist to interpret and think about the artwork on a completely different level. Both series became quite popular amongst artists. I am looking to do a fourth series in January 2020 now.

Our main show of the year is the Taragaon Lecture Series. We just finished our 7th series. Every year the foundation invites foreign scholars who worked in Nepal in the past. They are invited to the museum to give lectures and exhibit their work, and after the exhibition, they donate their work to the archive to make it available for the public to research.

Taragaon Museum is an architectural museum and the material we safe-keep in the archive are also mainly related to Nepali architecture. We are the custodians of these materials, therefore the idea and mission is to bring that out to the public. Through the museum, we are fulfilling that objective to a certain extent. Our next step is to make the archive available, and hopefully we would be able to do this soon.

Exhibition – Taragaon Lecture series 7, 2019

What are your challenges in playing so many different roles?

I don’t see such challenges because the mission of all the different institutions are almost the same. Through all these different platforms, I will still be working on exhibitions, displays, research and documentation. I don’t think I will be doing things any differently.

Tell us about the accolades and hiccups for your work so far. What was the biggest learning experience?

I am still in the very beginning phase of my race. Rather than receiving praise, I have always wanted people to point out my mistakes and failures, so that they can be my learning experience. When we started the museum, neither myself nor my foundation had an experience of running a museum.

Working in the museum from scratch is the biggest learning experience and this gave me an opportunity to learn every aspect of making and running a museum. I have always done a variety of different things and I believe that added an entrepreneurship element in me, which was missing in me before. Foremost, without the continuous support from the foundation and the trustees, I would not have gained this learning experience.

Open Studio – series 3 exhibition, 2019

How do you balance the contradicting elements of your work?

When you look at small museums in a small country, it is mostly about multitasking. If I was only just the director of the museum, I would not have been able to work with the contemporary art gallery and curate shows, I would not have been able to learn about archives, collections management and documentation and so many other such elements. I would not have been able to be so instrumental if I was just designated for a single task or a role.

We all juggle and ensure that we have time to do everything but I do not consider that I have a multi-hyphenate personality. I might be multitasking, but all the roles are similar, they complement each other, therefore I am able to work without contradicting all my workloads.

In an ideal world we should all have 8 hours of work, 8 hours of family time and 8 hours of sleep. 8 hours is my committed time in my professional life, which I cannot negotiate. Usually for most of us, the remaining 16 hours get negotiated. The commercial part still falls under my professional life. Therefore the 16 hours that are personal, can also become creative. And if we are able to manage this time cleverly, I think the spiritual part and physical element will also get addressed. Usually spending a bit of time in my studio or in my garden becomes like meditation for me. This is something that reenergises me when I lose my balance. My executive and managerial duties go in parallel with my world of art, and it somehow gets balanced.

Permanent Exhibition of Taragaon Museum

What is the primary role of curator?

This title in fact carries multiple other sub-roles in museums, galleries and exhibition spaces. For example, the role could make you the incharge of a collection, a researcher and it certain cases, also as the specialist of that collection, when it comes to a permanent exhibition. For a short period, temporary shows, and festivals, the role of a curator is being defined from a completely different perspective and I think this has a lot to do with the 21st century trends. Now we no longer rely on factual information or narratives. Because of social, cultural, political, environmental and other current issues.

The structure of storytelling has changed, there are lots of different ways we are narrating stories. Now predominantly, the major part is about understanding the content and context, so that one can create a three way dialog between the curator, artist and its audience. That is how I see this role.

I didn’t do museum studies. Whatever I have learned has been through my practice, understanding and research. It has been nearly six years since I have been in this role at the museum and I have spent hours and hours with artists and critics and people from the art circle. I did many curated shows at the Taragaon Contemporary art gallery, and what I have witnessed is, through my dedication and constant support I have provided to artists, I feel I have taken the museum towards the right direction.

Performance art: Kathmandu International Performance Art Festival 2019

Tell us about your curatorial process.

This is one of the questions I am asked quite often. Curation is not a deliberate process and it doesn’t have any formulas. That is why we always say curators start with something and they end up with a completely different result. My curatorial role is mainly focused within my museum only and I have not been exposed to bigger festivals and shows. I have been to several curatorial and museum training programs. Usually the knowledge acquired there becomes a main source for my curatorial outputs. I sincerely feel that my skills have polished over a period of time.

Each exhibition can be a challenge, but to try and implement what I have learned turns it into great satisfaction. Hence, my curatorial process is more of a homegrown and self-taught method.

Tell us about your inspirations, frameworks and references.

Inspiration could come from everywhere, and there are many things that inspire me everyday. I am inspired by nature and surroundings because it caters to everything I need, it fulfils the entirety of being myself. I am inspired by passion and dedication.

My best example will be my father, I always saw him being so passionate, dedicated, faithful and focused to his work. He couldn’t stay a moment without creative thinking, reading, writing and painting. Therefore, his way of working always inspired me.

Object in Focus – series 3, 2019, with visual artist Ang Tsherin Sherpa

Would it be safe to say that the Taragaon museum’s contemporary art gallery is your first step in the direction of manifesting your futuristic visions?

The creation of the contemporary art gallery was definitely a futuristic vision because it was deliberately conceptualized as a space to provide a platform for young and upcoming artists. But it was also a way to connect the audience with the permanent collection. As we are an architectural museum, the interest from the local audience has been always less. Our contemporary art gallery plays a bridging role to connect people with the architectural collection. Sooner or later it will definitely become a hub for young and upcoming artists. Since the beginning, we have designed this platform to be very approachable, therefore artists feel really comfortable to come speak with me directly. It is not only because of the open studio and other programs, people also adore our building architecture. There is ample space in and around the museum in comparison with other galleries in Kathmandu. Artist love to do performance art in our open spaces. There is so much we can offer to the artists, it is a multifunctional space. In the future, we are planning residencies also, and this could open up whole new possibilities for national and international artists from different backgrounds.

Tell us about the trends in art that you have seen over the years

I finished my BFA in painting in 1997, an age without the internet. At that time, we had few references and means to read and witness the art movement from around the world. Now, after two decades, I have witnessed big change, and there are many reasons why the trends in art have changed. The method has changed, the thinking is different, and artists are being very experimental. Now I see lots of influence from the neighboring countries, Europe, and the art movements that are happening around the world. This is also one on the main reasons as to how the current trend differs drastically from before the millennium. Now I find more and more artists are working with current social political issues, tradition, and indigenous culture. The art form has become more diverse and dynamic. It demands more dialogue because their conceptual ideas are being contextual than ever before. Artist are being multidisciplinary, which is allowing them to express themselves via performance, photography, video art, kinetics and installations. Artists are more aware now and being more articulate and thinking more critically. It is very promising, but at the same time, also worrying because of different factors.

I feel something may need to chang. We are not really in the world art radar yet, and we are still far behind when we compare our activities with our nearest art world scene of India and China. The art scene in Nepal, is still in many ways, about the artists living and working in Kathmandu. Outside Kathmandu, there still isn’t much happening. The good part is more galleries are opening, again this is more so in Kathmandu. Over the last few years, museums are being initiated by the private sector, and that is very promising for the artists. We are trending well, but there is still a long way before we get ourselves visible in the international art arena.

Taragaon Lecture series 7, 2019, talk program

Let’s talk about your most future forward project – the virtual Global Nepali Museum <www.globalnepalimuseum.com>

If it weren’t for my work at the Taragaon Museum, the Global Nepali Museum concept would not have incubated at all. The idea started with my love for heritage and culture that I grew over a period of time at Taragaon. The core idea behind this virtual museum is to document the artifacts that are displayed in different museums around the world. It is believed that almost 80% of such artifacts have actually gone outside the country in less than a hundred years of this time period. Some are displayed, some are in the museum’s storage and the whereabouts of some are totally unknown.

All these objects are recorded in this virtual museum. This is an ongoing project and data collection is single handedly managed. I have also been emphasizing that this virtual museum is not a campaign towards repatriation. This is entirely intended to record the objects for future generations. This is the first database of its kind, even the department of Archeology has not compiled such data in the past. This museum allows people to browse through categories such as sculptures, paintings & manuscripts, cultural objects, contemporary art, drawings and photos. All objects contain all the metadata that are made available by the owning museum. There are challenges about the data uses, which I am hoping many museums will cooperate and support this effort. The British museum is the first one to allow me to use their digital data from their site.

Tell us about your own personal evolution, on the journey so far.

From being an introvert, I have became very extroverted now, and that is the biggest change I have seen in myself after being in the museum. I have always told my well-wishers that being in London, I was disconnected with the art scene of Nepal for 14 years, but after coming to Kathmandu, I truly believe within these four years, I have gained what I may have missed and that is another positive impact I‘ve experienced in my journey.

I think this has been wonderful, I think I have a meaningful profession where I can connect with past, present, and the future.

Permanent Exhibition of Taragaon Museum

Which shows, performances and experiences have shaped your own creative process? Who are your maestros? Whose journey would you want to read about?

In terms of art festivals and shows, I am very much fascinated by big shows at Kochi, Art Dubai or the Dhaka Art Summit. They are remarkable. The scale of these festivals are truly magnificent that it even gives a lasting effect to the crowd that come from a non-art background. Their outreach is extraordinary. I love the art that is not usually restricted within a canvas frame.

I like the approach of Diana Campbell Betancourt, Alexie Glass-Kantor and Naman Ahuja. I always find they have the ability to go beyond by breaking barriers, I love the way they talk about shows, and just listening to them could give one so much energy to do more.

Recently I have started to see solo shows more, because I want to see how they dissect the content and re-curate it again in the same timeline. I have seen the solo shows of Antony Gormley, Frida Kahlo and William Blake at exhibitions. It is completely mind blowing how they’ve recreated that individual through different stories of their lives. I must say that this kind of inspiration I collect from such shows are definitely helping me shape my own creative thinking process.

I do not want to miss the Nigerian curator, Okwui Enwezor, who died this year. He is another curator I look up to. It is incredible to look at his portfolio, and the work he’s done around the world.

Studio and art work by Late. Manuj Babu Mishra

The Mishra Museum. (Studio of Manuj Babu Mishra)

My father was an eminent artist and art scholar of Nepal who passed away last year. He has written over 20 books about art and he had been continuously painting and drawing all his life. His collection is with me now and that is a big responsibility. My options were an easy one or a difficult one. The easy option was to sell them to collectors or institutions. The other option was to create an institution to be able to keep his legacy alive by telling his story. I chose the second option, therefore I came up with the concept to build a museum. Mishra Museum is a vision to preserve, display and exhibit the works by Late. Manuj Babu Mishra.

The collection includes his early works from Bangladesh, his paintings, drawings, sketches, photos, manuscripts and personal objects. In reality, I have everything for the museum, but don’t have a building.

Most of his works portrayed his own face and some of his recent work depicted Monalisa. Almost every morning he created one sketch and that was his continuous process for the last fifteen years. The collection includes a book full of Nepali artists and scholars, he sketched them live and they are countersigned by those individuals. Now, I am going through these materials again, I am managing them and also studying them to conceptualise different phases, stories and galleries. There is a lot to do, this is just the beginning.

Sagarmatha Next

At Sagarmatha Next through art and education, we will be working with waste, climate, and the environment. Basically, everything anchors around waste at this centre. The centre construction is nearly complete and we are looking to do a big opening in May next year. The centre has a film saloon, A VR room where we talk about mountains, flora, fauna, trekkers, climbers, Sherpa, climate, environment, etc. There is an indoor gallery where we will be inviting artists from around the world for exhibitions. There is a workshop where all the segregated solid waste from the region will come to the centre and artists and designers will be making art and products from it. There will be a shop, where all the products made from waste will be displayed. The centre has a small art park, which will contain installations and sculptures made from the Mt. Everest waste. The facility also has a residency space. At the moment, an education program is being collaborated, and in the future, we aim to hold conferences, mountain film festivals and other similar programs at the centre.

The area generates almost 400 tons of waste, mainly from tourism and it is not getting any better. Our centre will be working with a local organisation to manage and shift the waste from the region. Currently they either burn or bury the waste, because it can only come out of the region via air and it is too expensive to do so. Therefore, our centre has rolled out a campaign called ‘carry me back’ bag. We cannot stop tourists from coming to this location, instead we want to make them aware of the footprint they leave behind. Most tourists come here with a minimum of 10 -15 kilos of food and consumable items and travel back very light. We want them to support our campaign by carrying back the shredded pet bottles and aluminium cans and dropping them off at the collection point in Kathmandu airport. Each ‘carry me back’ bag contains about 30-35 shredded pet bottles. This campaign will help us shift the waste from one point to another without any cost. We are running a trial at the moment and it is working very well.

So far it is all going well. We have a team from Holland designing products, filmmakers from Sweden making films and VR contents are being designed for the exhibitions. I am mainly looking at the ‘waste to art’ project. Last June, we selected 6 young artists to make artwork from the waste at the Taragaon Museum and we selected 2 artists from that project. Next year they will be invited to the site to make artwork from the waste collected at Mount Everest. We are also inviting artists from other countries. We are in touch with many, but we have not confirmed it yet.

Before you go – you might like to browse the Asian Curator curatorial archives . Contemporary art curators and international gallerists define their curatorial policies and share stories and insights about the inner runnings of the contemporary art world.

Add Comment