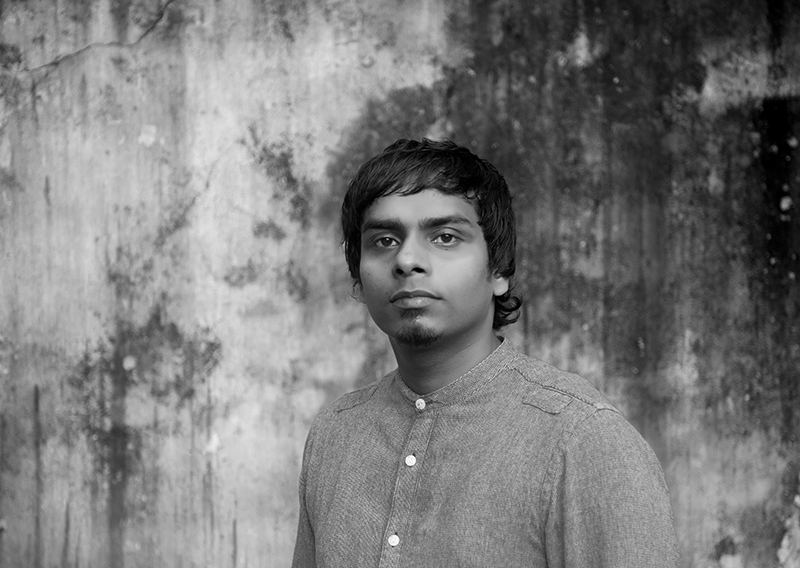

Pushpakanthan Pakkiyarajah talks about navigating the emotional landscapes of pain and trauma borne out of war, in an interview with Sonalee Tomar, for the Asian Curator.

I think art should mirror society. But mirrors can be deceptive too: they can give you strange deformations of reality; they can magnify some aspects or shrink them.

Featured image: Disappearance XIV.

Take us to the beginning of your story. How did your tryst with art begin?

I was born in Batticaloa to an artistically-minded family who first understood art as a form of entertainment. I grew up seeing lot of dead bodies in the streets and I responded to those experiences through my art.

As I grew older, my approach to art shifted to reflect the violent society in which I grew up, as a means to psychologically analyse the pain that I, and those in my community, have faced. I always drew trauma and violence in some form, but I didn’t know why until I started my studies in Jaffna University. I began to experiment with the content of my artwork, which helped me understand why I was drawing these images.

I studied art and design at the University of Jaffna, and I was lucky to have been taught by wonderful teachers like artist and historian Dr. T. Sanathanan, and P. Ahilan who is also an art historian and poet, among others. The programme introduced me to the wider network of artists from South Asia, which in turn allowed me to exhibit my work in the region through a residency in the Maldives in 2013 and in Colombo with the Asia Art Archive the same year.

Now, I aim to bear witness to the ever-present trauma from a distance and embed my artistic approach in a globalised context. Beyond the process of dealing with the past, I engage with the post-war space and ask: “What comes next?” As an artist, I often feel trapped by the burden of tragic histories even while moving towards reconciliation.

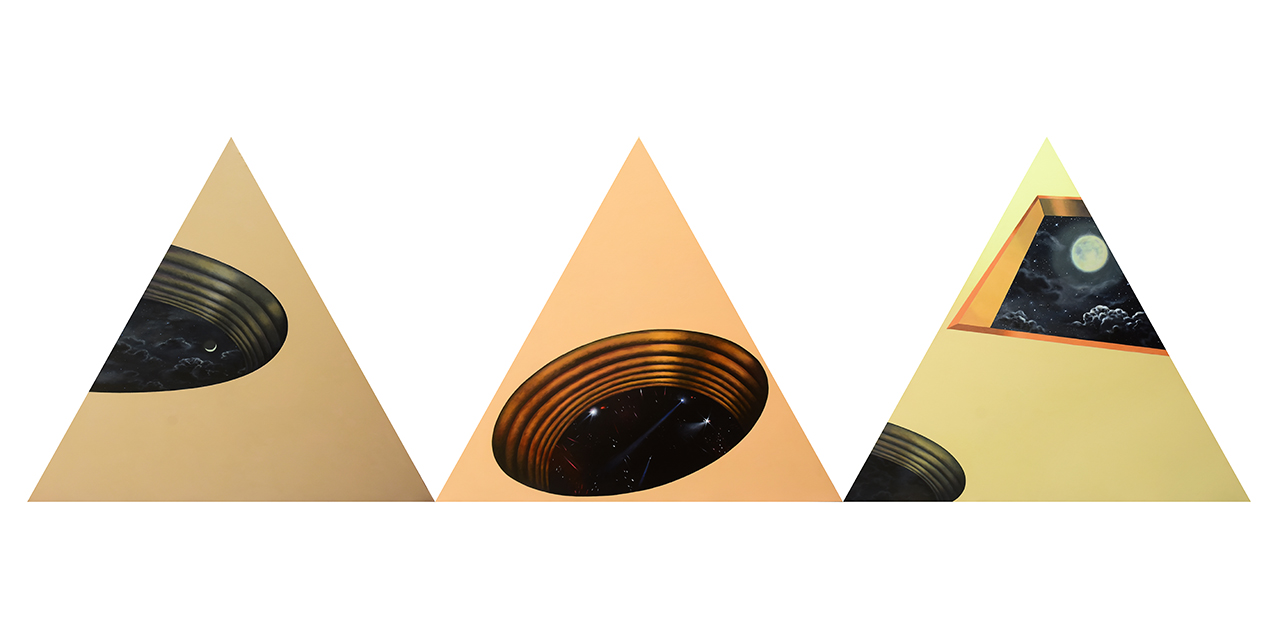

Sky Fallen Down.

What is the primary role of an artist? How do you describe yourself in the context of challenging people’s perspectives via your work and art?

I would hope that people are struck by my work; that they find it thought-provoking, rather than merely beautiful. If they only contemplate the aesthetics of the work, no doubt they will forget about it very quickly afterwards. But if they are impacted by my paintings, they will not forget so easily, and they will make them think. As I have said elsewhere, I think art should mirror society. But mirrors can be deceptive too: they can give you strange deformations of reality; they can magnify some aspects or shrink them.

Artists, in my view, have a social role. They are conscience-shakers who have the capacity to open people’s eyes and make them think. I am not very fond of the kind of artists who get more attention than their work, since for me artists are the mere messengers of the story. The artist should also cultivate their role as audience and not only as creator, since it’s the only way in which can they understand the extent and ways their art is received.

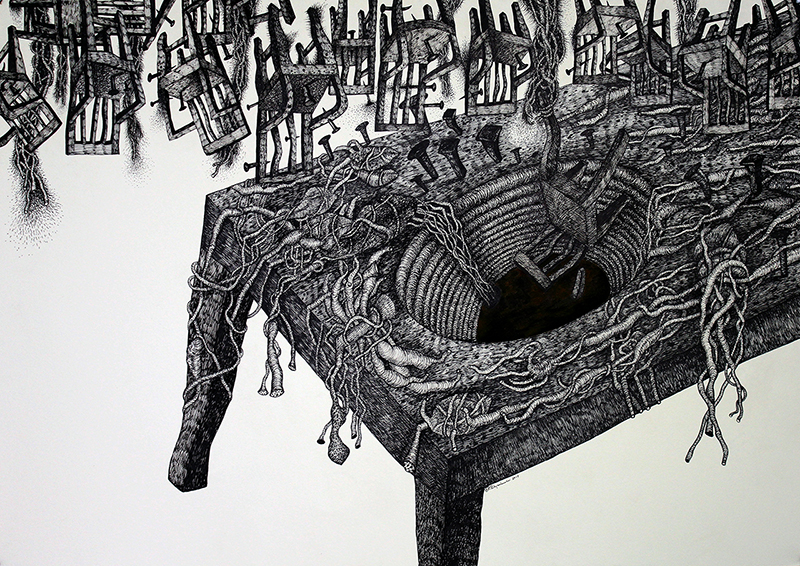

Disappearance IV.

Let’s talk about your career. What were your biggest lessons and hurdles along the way?

I have had plenty of wonderful opportunities during my career and have always tried to learn from all of them.

The first landmark in my career was to be able to attend Jaffna University and have the fantastic chance to work under the supervision of Dr. T. Sanathanan, who was my mentor and became a primary influence in my work. Also, he introduced me to other recognised artists such as Muhanned Cader, Prof. Chandraguptha Thenuwara, Prof. Jagath Weerasinghe, Kingsley Gunatillake, Prof. Sarath Chandrajeewa and more, who have all inspired me to practice and work hard.

While I was in Jaffna, I had the chance to go to the Maldives to take part in the SAARC Artist Camp and Exhibition of Paintings. I was lucky enough to work with Sharmini Pereira on a wonderful project called Open Edit, Mobile Library conducted by the Asia Art Archive and Raking Leaves. I also did an exhibit called Seven Conversations as part of a group with my colleagues, which was curated by Sharmini Pereira and Dr. Sanathanan at the Saskia Fernando Gallery. My participation in Shadow Scenes during Colomboscope in 2015, which was curated by Natasha Ginwala, was also an important step in my career. Udayshanth Fernando and Saskia Fernando gave me the opportunity to exhibit my work four times in their prestigious galleries – Paradise Road Gallery and Saskia Fernando Gallery – where I worked on social issues. I am interested in providing a public space for open discussion through my work. My participation in the arts residency and exhibition Young Subcontinent, curated by Riyas Komu at the Serendipity Art Festival in 2016 taught me to approach the work and experiences of other artists from the subcontinent through their art.

One of the most memorable moments in my life, undoubtedly, was receiving a fellowship as a visiting artist at Cornell University in 2018. I immersed myself in the university’s rigorous academic environment, working closely with graduate students across disciplines, and members of the staff such as Prof. Iftikhar Dadi, who was my mentor during my stay and an invaluable source of inspiration. I also had the great opportunity to give a talk on the history of the art gallery and open my exhibition entitled The Disappearance of Disappearances. My friends Kaitlin Emmanuel and Piragash Swargaloganathan helped me lot with this show.

The Herbert F Johnson Museum of Art collected a triptych from these pieces for their permanent collection. This fellowship challenged me to contextualise my work within global histories of war and displacement. At this time, Nedra Rodrigo invited me to do a two-man show and artist talk, and to conduct a workshop in Toronto, with the support of the York Centre for Asian Research at York University, which was also a good platform to make meaningful conversation outside of the island.

Another memorable moment in my trajectory as an academic was the coordination of the First Degree Show under the supervision of Dr. Mariah Lookman, at that time a consultant at our department. It was very well received and a few of my students were selected to exhibit at Theertha International Artist Collective and will exhibit again at the University of Dundee in Scotland this year. So the upcoming generation of Sri Lankan artists will also be able to express their views on present-day Sri Lanka.

Being nominated as a principal candidate by the Fulbright Program to pursue a Master of Fine Arts for the 2020 awards has been an enormous honour, as well as a rewarding experience, from which I have already learnt a lot.

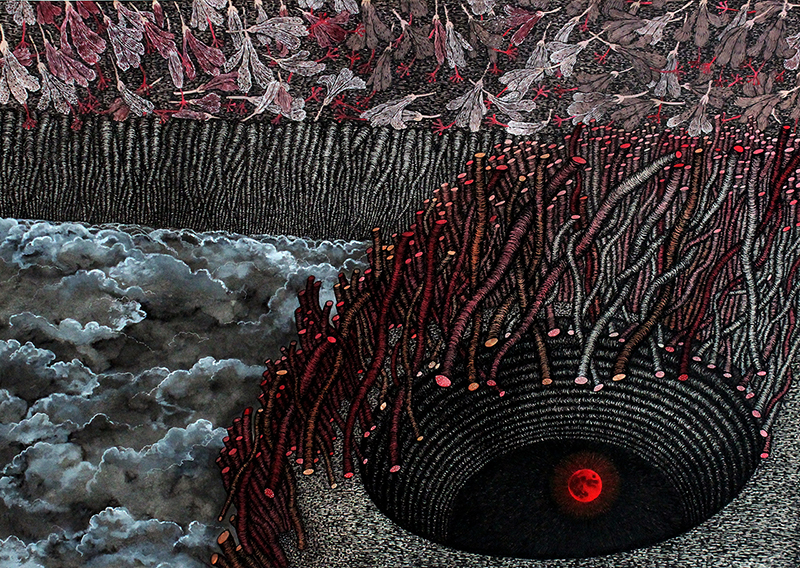

Wounded Landscape I.

My creations express themselves as the psychological analyses of the reactions that suffering evokes in me.

Let’s talk about your frameworks, references and process. What inspires you?

Most of my creations depict experiences and discourses that have tragedy as the underpinning, all-consuming theme. Rather than the healthy and pleasant events in life and in society, incidents of intense hurt and screaming, physical and mental suffering, compel me more due to the deep and prolonged pain my country is emerging from. My creations express themselves as the psychological analyses of the reactions that such suffering evokes in me.

Nevertheless, I am trying to observe the ever-present trauma from a certain distance and embed my artistic approach in a globalised context by exploring ideas relating to agency, identity and gender.

Therefore, in my role as an artist I express my generational outlook, a subtle feeling of being trapped by the burden of a tragic history, of being in search of reconciliation, and of experiencing cultural in-betweenness.

While I don’t yet have answers to any of these questions and tensions, through refined shifts of perception in my art, the spectator is able to empathise with the feeling of loneliness and what it means to be forced to start one’s life all over again.

My art grapples with the emotional torture families endure as their questions persist, unanswered. Haunting memories, imagination and fear fill my work as suffocating mental constructions that strangle those imagining the suffering of their family members and their own inability to help them. They are trapped between surrealism and reality where disappearances themselves disappear; they vanish from political discourse and from collective memory. They disappear behind ethnicised politics yet lurk as spectres of injustice. My work recognises the human need to situate and share this suffering within the context of the suffering of others. My drawings depict the wounded landscapes by filling a white space that signifies the void left by the whitewashing of disappearances from history, landscape, and everyday lives.

Wounded Landscape II.

Are you more of a studio artist or naturally collaborative by nature? How do you feel about commissions?

I think of myself primarily as a studio artist and I love to bring the surrounding nature to my studio. Indeed, solitude is essential to me since I become more inspired to work on my own and try to transform all the pain and trauma I have experienced in art since, to me, it is a therapeutic, healing but also an individualistic process.

However, I am also open to interesting collaborative projects that look appealing and challenging. I love to work in collaborative projects since they give me the opportunity to learn from others. It’s true that collaboration is easier, sometimes only possible, if you share the same conception of art with the rest of your colleagues though different realisations.

My first collaborative project was a called Contemporary Artists Meeting Point or CAMP curated by Prof. Chandraguptha Thenuwara and Dr. Sanathanan, together with other Sinhalese and Tamil artists. That project allowed me to immerse myself in the others’ personal stories. During the walk across the sands of Mullivaikkal beach, over the graves of those taken in the final phase of my country’s civil war I came upon a charred-black album, the photos burned and the faces obscured. With what hopes was this album brought to this place? The album and its memories haunted me, and I started to burn my own drawings and create shapes with the fire. This became a mixed media series I exhibited, entitled Burning Memories. The result of that collaborative work was exhibited in Colombo as the outcome of a project that brought us all closer, through sharing our traumatic experiences, in the workshop and exhibition.

Currently, I am taking part in a collaborative project called The Packet along with nine other Sri Lankan artists from different fields, working together in an innovative concept about the artistic community as a common space to talk about socio-political issues in contemporary Sri Lanka. My contribution there was a piece called Belt, Wounded Landscape, Land for Sale, which was recently exhibited at the Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa, India.

Another project I am very lucky to be part of is the TAASI East, which is a research and learning institution in the city of Batticaloa, Eastern Province, Sri Lanka under the direction of Prof. Elizabeth Dean Hermann and Dr. Dushyantha Large. My role there is to be the director of student recruitment, visualisation, mapping and 2-D design.

In relation to commissioned art, I have been approached on many occasions to take that kind of work but I have always rejected the idea. As an artist, I want to feel free, being only constrained by the impositions of my own mind rather than by others.

As a young art student, I had to take some commissioned work to survive and manage my career, but after I finished the work I felt I had to satisfy the customer’s wishes rather than my own. So, as soon as I became financially independent, I decided to follow my own tastes.

Disappearance XIV.

The inherent question then is what is “beauty”?

How does your audience interact and react to the work you put out into the world? What is that one thing you wished people would ask you but never do?

People usually tell me the love my work and appreciate the quality of it. They like the black and white contrast and the fabric like texture of the lines that are interpreted as roots or veins. When they walk through my work they tend to think they cannot look at it for long because they become too sensitive to the reality of pain I try to express. They have also told me they like my work but they would not be able to hang it on their walls because of the pain it conveys. My art is deeply rooted in Sri Lankan history but the scope is as universal. People identify their own trauma through my work.

As an anecdote, I can tell you what happened to my mentor and friend Nedra Rodrigo. She has one of my works, and her child Rafael could not bear it, since he was scared at the sight of it. Nedra tells me she has to keep it aside until he is more grown up and able to face it. I also have heard from his mom that Rafael began crying and ran away from an exhibit of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work at the Art Gallery of Ontario. This is the place where I point out that we have always only thought of art as a conversation between adults, and not thought about how children receive it.

Some people have told me that I have the craftsmanship to take on more beautiful subjects, but my mind is always struggling with a particular type of subject. The inherent question then is what is “beauty”? People tend to praise the technicality of my work, the extreme detail or the intricate lines, but I have always been inspired by local craftsmanship, the mat weavers from my village in Batticaloa. To me that process of creation is like meditation and a way of healing through art.

Also, some people want me to suggest solutions to these social problems, but I am just an artist capturing reality through my eye and experience. I am not entitled or even able to offer them solutions, while they can perhaps find them through critics and their own understanding.

Disappearance XIV.

Before you go – you might like to browse our Artist Interviews. Interviews of artists and outliers on how to be an artist. Contemporary artists on the source of their creative inspiration.

Add Comment