Priyanshi Saxena talks about breaking the colonial mindset, looking at art through a fresh, diverse lens and decentralising the art market.

The constant notion of canonising western, specifically European, art history and aesthetics is extremely problematic, and pains me. The attempt through IAM is to identify and strengthen the inherent aesthetics and tastes. It gives me great joy to discover art that isn’t being judged on western barometers, and instead by parameters that I share some cultural history with.

Mohan Naik, Rocky Pastures 2, oil on canvas, 24 x 32 inches.

Take us to the beginning of your story. What was your first interaction with art? How do you describe yourself in the context of challenging people’s perspectives via your work?

I started my career dabbling in writing for a newspaper and working in advertising, while studying at St. Xavier’s College in Mumbai. Then life took a slightly unreal turn, and I joined MTV, and ended up working on producing reality television. This experience pushed me away from working in mass media, and I explored possibilities in fine art – attempting to show art in non-galleried spaces, but failed despondently.

With a little help from some friends, I went to study art business at the Sotheby’s Institute in New York. I followed this by working with Christie’s in the Post War and Contemporary department, and worked with a couple of other small art organisations in New York, to get a taste of how a developed art market works. The taste didn’t really grow on me and I started craving the art I understood and loved.

Back in Mumbai, I worked for what seemed like a fleeting second with an old school friend, looking to diversify the portfolio offerings. The learning from there was that the traditional trader doesn’t really value an asset whose growth trajectory cannot be mapped by data.

This opened the doors to one of a great learning platform: I worked with one of the best galleries in India – Project 88 – which turned out to be a true alma mater. I worked on programming, artist management, acquisitions, art fairs et al and enjoyed every bit of it thoroughly. This also exposed me to how best business practices can be put to work in reality, and how an organisation can run on track. Then, with the help of the director at Project 88, I moved to working with the The Gujral Foundation and Outset India in Delhi, curating and programming their space in Jor Bagh, as well as working on the collateral project ‘My East is Your West’ at the 56th Venice Biennale.

This was succeeded by a quick consulting gig with a modern art gallery, till the dawn of the realisation that I enjoy working on both the curatorial and the business aspect of the art world. Through the entire process, I learnt of the fissures in the Indian art market. That led to developing Indian Art Market (IAM).

Suhas Shilker, Untitled (2018), acrylic on canvas.

Take us through your process that led to the birth of IAM. Feel free to mention other work.

When I was working in the art markets in Delhi and Mumbai, I saw homogeneity in the art displayed. It seemed to cater to western aesthetics and markets. There was also a sparse representation of artists from non-metropolitan cities. Considering the supply-demand ratio – about a lakh art students graduate every year, and we have less than hundred full time art galleries in this country – I realised the need for the market to grow, and in a sustainable way.

Thus, the idea of IAM emerged. It is a three-pronged approach: to expand, refurbish and re-strengthen the regional art markets in India, while creating a sustainable environment for it to grow, through fostering demand for art in tier B cities. We want to achieve this by studying and understanding the regional art markets and tastes. We wish to diversify the collector base by indentifying mid and low-budget collectors, and have interventions that remove language, class, caste, taste and geophysical barriers to buying art and activate the existing demand and build a new customer base. IAM believes that everyone is a collector and all tastes in art and aesthetics are legitimate. The three pillars of this approach are:

GrAF (Grid Art Fair): We have art fairs across tier B cities in India, to provide an equal platform to showcase and sell art for everyone, including craft and tribal, in the contemporary art market.

Dvaar: We develop skills in arts business, management and leadership.

MIA (Mapping Indian Art): We bridge the information void, and open up access to all art avenues through digital and make dynamic art maps accessible in local languages.

Francis D’souza, Untitled (2014), pen, ink and watercolour on paper.

What inspires you? How did you deal with the conceptual difficulty and uncertainty of setting out to create something that no one else has aspired to?

When I look at the diversity in other mediums of art like literature, theatre, music and so on, it leaves me yearning for a platform to explore more of our inherent art. Also, the constant notion of canonising western, specifically European, art history and aesthetics is extremely problematic, and pains me.

The attempt through IAM is to identify and strengthen the inherent aesthetics and tastes. It gives me great joy to discover art that isn’t being judged on western barometers, and instead by parameters that I share some cultural history with.

Doing this is difficult, as one has to break the mould set by colonial institutions and their residues. We speak in a language that can’t even describe all our food well. It is difficult to break those shackles, and get people to be more confident of diverse modes of art and culture.

How did it all come together? What were the biggest challenges?

The biggest challenge of all is the scale and scope of this project. To be able to build sustainable fairs, and therefore markets in about 26 cities in India is the most daunting prospect. The most common reaction to me presenting this project to anyone is, “It’s ambitious!”

Also, the timing of the launch is a little unfortunate, with the economy in a slump. Being a nascent market, with not too much data to back it, it is extremely reactive to economic cardiograms. It’s important to have a mature and developed art market that caters to a variety of purchasing powers, and therefore can be hedged against the uncertainty of the general economy.

Lastly, the toughest barrier is breaking through the mental barriers of artists, collectors, potential collectors, and even audiences.

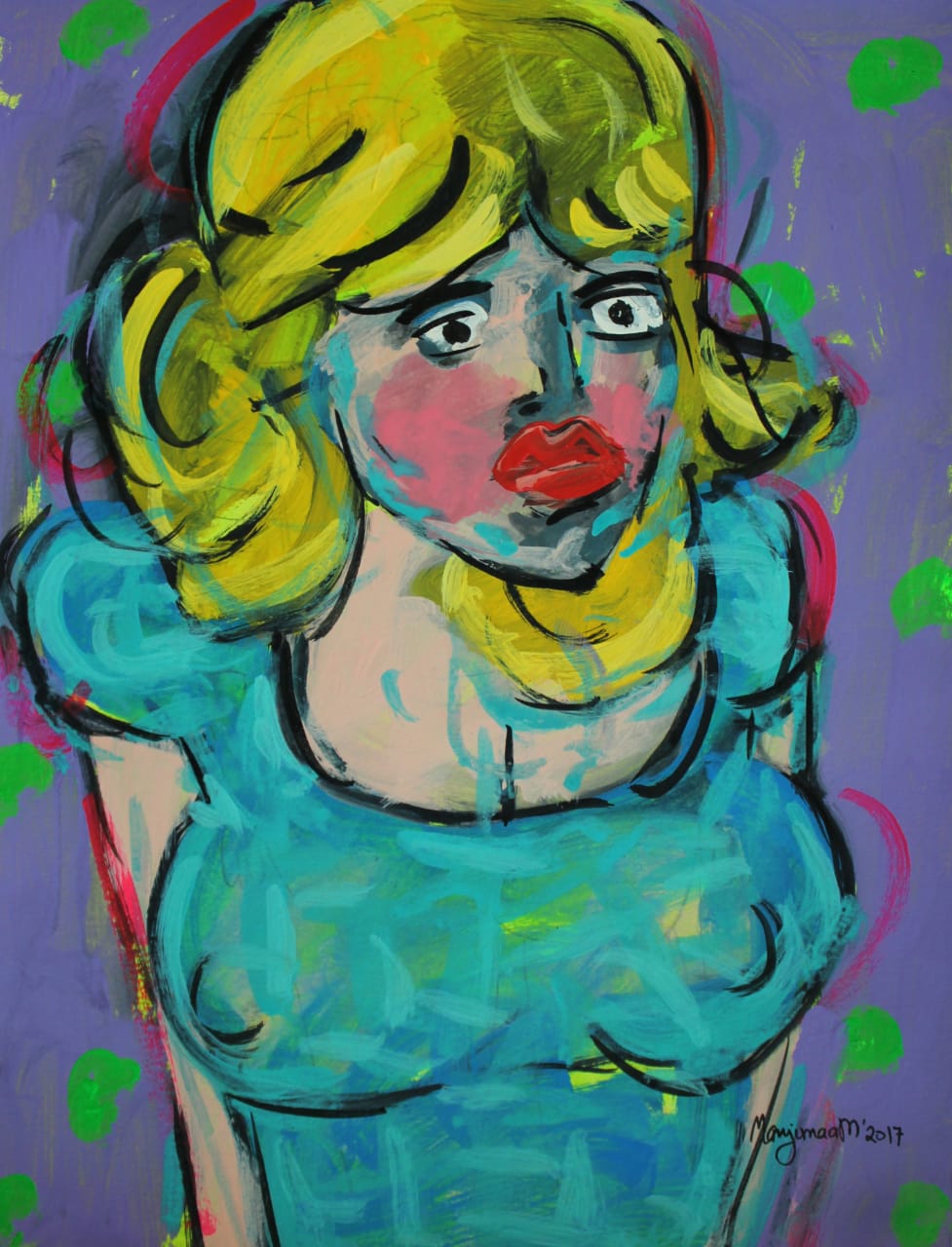

Manjunath Naik, Untitled (2017), acrylic on paper.

Who are your maestros?

I have been fortunate to work under amazing women, who have themselves been part of shaping the trajectory of the Indian art market. My first boss in India, Sree Goswami who is the director of Project 88, is someone who has been a second alma mater for me, showing me how to practice ethics, and employ good practices.

Feroze Gujral, the director of Outset India and Gujral Foundation, for her ability to dream in scale, and realising them, and supporting young and emerging voices.

Farah Siddhiqui, the director of FSCA, for her ability to break the mould and actively work on diversification of the idea of art, of the collector, and even the market.

Lastly, because I want to build markets, especially through fairs, I really look up to Jagdip Jagpal, for being able to structure and scale the fair, and penetrate art markets beyond the metropolitan cities.

Vaishali Oak, Untitled, 2018.

How do you balance art and life?

It’s easier for me because art is a huge part of my life and I am one of the biggest consumers of art! And honestly, I get by with a lot of help from my friends. Art is my work, but it is also my passion and joy.

How does the market react to your work?

Different markets have reacted differently. Goa, which has been a thriving market, reacted very kindly, whereas Pune was a bit bland – which goes to show that you cannot standardise your approach to building markets. The ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach has been busted. Places are diverse, they have unique histories and futures, and it is important to understand that demand in each city. Our approach to each city or market is tailored to the idiosyncrasies and vacuums of that particular region.

Are you collaborative by nature? What are the some of the formative collaborations you have been a part of?

The art industry is a very collaborative industry. By its nature, art cannot function in isolation. It needs an audience, people who support it, who engage, who can help it evolve.

Being a largely unorganised sector, we need each other to get by. Friends from within the media help with publicity, friends within the art exhibition making space help build shows, and I have even found artists through friends.

There have been conversations about formalising this friendly collaborative space, into a structure, like a union, where the entire entity can formally aid and assist one another, especially in terms of working rights and conditions.

Suhas Shilker, Untitled (2018), acrylic on canvas.

What are your observations vis-a-vis the Indian art market?

The Art markets in metropolitan cities in India are saturated. There is wealth and histories of taste and collecting in tier B cities, which are mostly capital of erstwhile princely states.

Also, expanding the collector base to the middle class, IAM is looking to build an art market that mends the fissures and vacuums in the current structure which is heavily centralised leading to the concentration of wealth and circulation of art in traditional zones of power. IAM aims to turn this structure into a centrifugal movement outwards – from tier B to peripheries, where art can exist in the daily lives and homes of people. Look at Raja Ravi Varma prints. Their profusion and proximity to people and their inclusion in the innermost recesses of Indian homes is widespread. IAM aim is towards this. IAM sees ‘taste’ as a democratic category, and not a marker of distinction. We wish to puncture the hierarchy of taste. Contrary to popular perception, people have a strong sense of what aesthetics appeal to them, and IAM aims to engage with that innate sense, rather than validating a singular discourse of what makes art ‘good’.

Also, the market is very top heavy. IAM is looking at expanding the scope of the market and creating an army of middle class buyers. This will take dissolving certain barriers of entry, and creating markets that cater to certain languages, price points and cultural milieu, among other things.

Tell us about your own personal evolution in relation to the work you do.

I look for conversions and first time buyers – people who are intrigued but perhaps have been alienated by the many barriers that exist to keep art centralised.

I understand and appreciate Indian art more and more every day. I am delighted to have the confidence to form my own opinions about art, and voice them as well. I appreciate the diversity in the art world, or the diversity I ache to achieve through collaborations, exchanges, new formations that disrupt entrenched norms.

What are you working on now? What should we look forward to?

After the success of the SEED fairs, which are smaller exhibition format fairs in Panjim, Goa, and Pune, Maharashtra, 2018-19, we are really excited about launching five GrAFs in 2020-21, in Goa, Lucknow, Jaipur, Hyderabad and Indore.

We are also in talks with some of the biggest players in the Indian art market so we can extend our skilling programmes being launched in tier B cities. Look out, Dvaar is soon coming to a town near you!

Before you go – you might like to browse the Asian Curator curatorial archives . Contemporary art curators and international gallerists define their curatorial policies and share stories and insights about the inner runnings of the contemporary art world.

Add Comment