Greek curator Maria Nicolacopoulou is inspired by work that is able to activate, negotiate and operate on all levels of perception.

The core notion of ‘contemporary’ rests in its ability to stay fresh and self-subversive. The moment you become confident and settle in yourself, you become redundant.

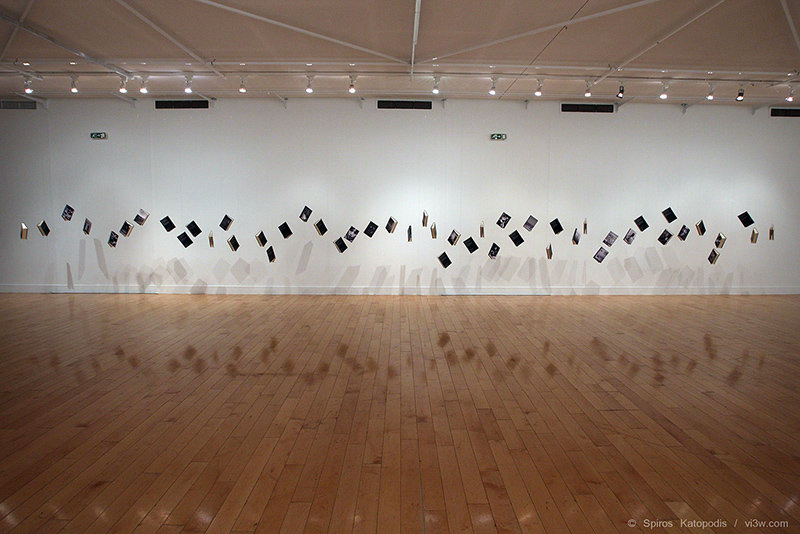

Featured image: Photo-graphē exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens. Opening night. Image credit: Spyros Katapodis.

Maria Nicolacopoulou. Image credit: Georgia Kotretsos.

In a critical profession, self-critisicm is key, the same way admitting failures and mistakes is, in remaining contemporary.

How do you describe yourself in the context of challenging people’s perspectives via your work?

By remaining constantly inquisitive, open to re-invention and questioning myself throughout the process – just as the core notion of the ‘contemporary’ rests in its ability to stay fresh and self-subversive. The moment you become confident and settle in yourself, you become redundant. After the culmination of a project I always ask people what they didn’t like rather than what they liked in the show for instance, as I always find it has more value. With sync’s projects revolving around research on the conceptual notion of an institution, its structure, format, public role and social responsibility, we always have to be ready and alert to apply the findings. In a critical profession, self-critisicm is key, the same way admitting failures and mistakes is, in remaining contemporary.

Photo-graphē exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens. Opening night. Image credit: Spyros Katapodis.

What does your role at Sync Residency involve? How do you balance the contradicting elements of your work?

Sync is an experiment founded on the premise of exploring the possibility and potential for institutional collaboration on a global scale and, as an experiment, it is prepared to accept its fate whether it is successful or not. The result would also be a testimony to the condition of the local scene, as it will be documented on the site in the form of a report after the program concludes. This initiative is the result of years of academic and empirical research on the nature of the institution of contemporary art, and what is that which makes an institution contemporary within the practical and conceptual challenges of an everchanging globalizing world.

I am responsible for all sync operations at the moment, together with the support of a funder. The current format is invitational for an international curator to come and conduct research in Athens. Once the curator is confirmed, they are matched with an existing non-profit fitting their respective practice, and they work together towards a final project. Being nomadic allows freedom, innovation and diversity, while it extends network opportunities and helps us remain experimental. A jury of advisors from previous fellows is also part of the plan, which would allow me to apply the open call format at some point. Ideally I would like to have the opportunity to bring a fellow from every part of the world, whether they are natives of a place or scholars with a specialization in that specific geolocality. The program started with guests from the US and Europe, and I am now turning to Asia, Africa, South America and so on. The idea is to be able to open channels of communication with parts of the world that Greece doesn’t generally have conversations with, and explore if and how we can find common ground in social, cultural and political structures, towards the potentiality for collaboration across the board. In the case this turns out to be not possible, dealing and accepting the shortcomings, inabilities and challenges of this venture, is what makes the effort precious in its contemporary sense, as it provides key information towards future institutional practices.

What is particularly challenging running this, is to try to be an administrator and a curator at the same time. If horizontality is an unkown term for most and isn’t followed or applied by everyone, trying to manage an organization, while attempting to apply horizontal curatorial practices, doesn’t work. This is mainly because the scene is small and therefore highly individualistic and competitive, so collaborative practices are only just starting to proliferate, mainly through the new generations. On the positive side, the size of the organization gives me the freedom to apply changes as soon as they are see fit, without lengthy processes found in large institutions, remaining in that way truly contemporary.

sync Curatorial Fellowship at the Swedish institute in Athens, November 6, 2019. Photo credit: Alexandra Masmanidi.

Tell us about your curatorial philosophy. How does it all come together?

Working with, and including, all mediums in a project is key, as I believe they all offer a uniquely different piece of information for a more comprehensive message – proliferation of one medium over others creates disjunction and ruins the balance. Curatorial work is like solving a puzzle: my job as a mediator when I am given a message in fragments, is to find a way to put the pieces in the right order, at the right time, to interpret the message accurately, so being fluent in everything that planning a show requires, is critical – from hanging works, to writing, to dealing with sponsors, to conceptual thinking, to outsourcing printers, catering, etc. If even a few of the puzzle pieces are placed wrong, the overall result is scrambled. I still remember my first couple of projects where I was riding in the moving company’s van next to the driver, to go pick up and drop off each of the works, while having to stop at the printers on the way to pick up the exhibition pamphlets I had emailed over a few nights before! A good professional must have hands-on knowledge of all the processes involved. We all too often see how being a strong scholar with a limited sense of aesthetic abilities or a lack of planning skills, or the other way around, unfortunately renders a haphazard result and an equally scrambled message.

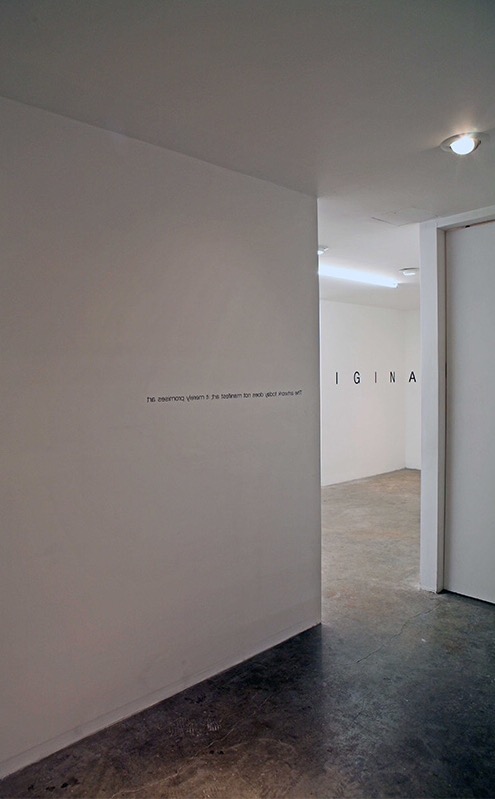

Uncurated at the Scaramouche gallery New York. Photo credit: Be Andr. The mirror piece is another Boris Groys quote and reads: “The artwork today doesn’t manifest art, it merely promises art.”

An inspiring example, is from the time I worked at Tate Modern, where its director at the time, Vicente Todoli, would greet all Tate staff, from interns to café employees, every day, regardless of how busy or where he was, in the most cordial manner, and this awarded him the respect of a great leader more so than his title did.

Let’s talk about your frameworks, references and process. What inspires you?

Being familiar with all parts of a project is also key because it allows me to work well collaboratively and horizontally with colleagues from all areas associated with a project. Collaborative practices are not only more productive, it is also the direction where curatorial and all artistic methodology is moving towards – the star curator culture is becoming redundant in light of more democratic methods in an effort to combat the industry’s insularity and financial constraints. With horizontal practices posing questions regarding individual authorship, the integrity of the project as a whole becomes more important than personal credit, which is why it is important for me to work with people who share a similar work ethic – it is very easy to forget that art is a humanitarian science and, as part of the humanities, it is directed towards the human at large, first, rather than oneself or one’s career, and this is where most lose their way and compromise professional integrity for the sake of personal ambition. So to be true to art, as well as in many other of the humanities, being a good human is as important – if not even more so – as being a good professional. An inspiring example, is from the time I worked at Tate Modern, where its director at the time, Vicente Todoli, would greet all Tate staff, from interns to café employees, every day, regardless of how busy or where he was, in the most cordial manner, and this awarded him the respect of a great leader more so than his title did.

Photo-graphē exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens. Opening night. Image credit: Spyros Katapodis.

What were you working on when the lockdown was announced?

We were in the middle of our third fellowship edition and ten days away from the final project when we had to flee fellow Ilaria Conti to Rome in advance of the flight shut off as all flights from Athens got cancelled.

How has this affected your practice and plans?

Fortunately we were able to adjust the project to a digital format, which gave us the opportunity to reach a wider and more global audience. On the downside, it is unsure if the upcoming fall fellowship will move forward and next year’s program is pending developments as, at this stage, nobody can plan safely for the upcoming year. I am sure that there are twists in the mix, which will prove to be quite beneficial so I am not too worried with the unexpectedly enforced changes.

Photo-graphē exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens. Opening night. Image credit: Spyros Katapodis.

Even though we don’t like the art world’s insularity, we remain in it because it is the last place of freedom.

– Alfredo Jaar

Which shows, performances and experiences have shaped your own creative process? Who are your maestros? Whose journey would you want to read about?

There have been only a few life changing instances in my life which have shaped my thinking and approach, and they were both by Latin American artists. The first is more serendipitous than anything, as whenever I have been at a crossroad, and in search for answers, I happened to be at a city where Alfredo Jaar was giving a talk. In every one of his talks that I went to, his response to a question from the audience affected my life, my work and my perspective from that point forward in a tremendous way, leading to what I do today. Characteristic is a quote of his, from the last lecture I attended in New York’s Cooper Union a few years back, where he said how “even though we don’t like the art world’s insularity, we remain in it because it is the last place of freedom.”

Another instance is the work Shibboleth by Doris Salcedo, which was a Turbine Hall commission in the year 2007-08, otherwise known as “The Crack” in Tate Modern. The work’s deep social and political poignancy, juxtaposed against its visual subtlety (compared to the rest of the Unilever spectacular Turbine hall commissions) in combination with the impact of its interactive element (people tripping and falling) and the fact that the work is still there in the form of a scar, testifies to the reach a work can have on a conceptual, emotional, theoretical and physical capacity, across history, time, as well as various areas of culture and sociopolitical life. From the historical impact of racial inequality to its application in contemporary society, the institution and the art world, the work’s interconnectedness shared by all these conditions is witnessed in the physicality of a visitor’s potential fall, testifying in that way to the subtle density of danger these invisible nuances can have in our lives, as well as art’s power in depicting them. A work able to activate, negotiate and operate on all those levels of perception, is truly inspiring.

Uncurated at the Scaramouche gallery New York. Photo credit: Be Andr. The long wall text is a Boris Groys quote that reads: “If reproduction makes copies out of originals, installation makes originals out of copies”

Tell us about your own personal evolution, vis a vis the work that you do. What have you observed re the changing cultural landscape over time?

My first curatorial project was in 2009, in the former embassy of Sierra Leone, in London, which was also a notorious party venue, at the time, and later the set for the film, The King’s Speech. The show, which explored issues of debauchery, got so unexpectedly full that we had to turn people away at the door due to health and safety hazards. As a result of this project, the space was introduced to the art world, and more shows followed there. My next project was an intervention at the oldest, and fully operational, civil courtroom in the UK, located in London’s City center. The show, through the use of all artistic mediums, confronted the notion of hypocrisy versus political correctness and lasted for a weekend. Working as a freelancer at Tate during this time, helped me fund those projects myself, together with the help of various sponsors and collaborator friends.

I then got an opportunity to work with the Director of Visual Arts at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, in San Francisco, which turned out to be a life changing experience. This is where I was introduced to horizontal practices, and where I realised what a true institution of contemporary art looks like. Apart from having the opportunity to curate various programs and work with artists like Mark Bradford, Jeremy Deller, Tania Bruguera and Rabih Mroue amongst others, I was part of a non-hierarchical team structure, where cross-departmental collaboration was the norm, the community and civic engagement a priority and the focus targeted on local issues with a global reach. I had always been interested in the big picture and always been looking for ways and methods through which cultural change could be implemented, on a large scale. As my experience was growing, I started looking into opportunities for more substantial cultural impact and how the application of curatorial skills could be applied on a larger context. Having experienced the impact of YBCA’s impact in the city’s cultural life, it was clear that change is accomplished through the impact of an institution’s mission, structure, audience approach and programming as a whole, rather than with selective exhibition making, which led me to pursue this further, with another MA in Museum Studies at NYU. Through intensive research, study and stellar professors, together with conversations and interviews with experts, like Laura Raicovich, Charles Esche, and Maxwell Hearn, amongst others, combined with experience working in organisations like Creative Time and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Modern and Contemporary Department, I was able to not only conclude that an institution holds immense power for significant cultural change, but I also narrowed down the main formats and elements required for it to be truly contemporary. An interesting finding, for instance, was the fact that the recent rise of technology and the subsequent social alienation it caused, led to the proliferation of socially engaged and participatory art practices as well as an elevated need for publicness and use for public space. I presented my findings in international conferences, where I received precious positive feedback.

Sync is based on that research and the specific needs of the country. Greece has a historical tradition in performance and theatre more so than visual arts, and contemporary art in particular is a relatively new thing, to which we find its small scene testifying to. Consequently any new trends in contemporary art can be found in small non-profits, and artist run spaces, as there are no major institutions dealing predominantly with that subject. Therefore, to help alter the core cultural mechanisms of the system, mere exhibition making would be insufficient – a different format was called upon to assist in the progress of the field here. So I founded sync in 2018 as a way to connect the local scene to the latest developments worldwide, through the collaboration of the small local forward thinking spaces. Apart from the fact that there was no other international curatorial fellowship program at the time, horizontal practices are still also very uncommon, due to the small size of the scene and the subsequent degree of competition present, so by attempting to implement a unique and nomadic programming format, the hope is that we will be able to not only help local artists connect with the global discourse and widen their network and conversations, but also introduce new methodologies for curatorial, artistic and institutional practice, while remaining experimental and, consequently, contemporary.

i YBCA is a multi – disciplinary institution with different departments hosting contemporary art, performance and film

Before you go – you might like to browse the Asian Curator curatorial archives . Contemporary art curators and international gallerists define their curatorial policies and share stories and insights about the inner runnings of the contemporary art world.

Add Comment