Contemporary artist Kira Nam Greene represents freedom and strength via her portraits of strong women interlaced with complex patterns that echo the feminist legacy of the ’70s

I like the term “cultural workers” as a designation for artists. I believe that artists are like canaries in coal mines, who are the first to ring an alarm whenever any socio-political injustices occur. Artists are both the mirror and the distiller of the society and culture we live in.

How did your tryst with art begin?

I always loved drawing and painting. Growing up in Korea, I never thought I could become a professional artist as I did well in academics. The stereotype is that art is supposed to be a hobby not a serious career.

Later, I moved to the United States to earn a doctorate in political science from Stanford University. When I was doing my Ph.D, I realised I did not like the narrow focus required for academic research. Living in the US opened my eyes to many possibilities.

In Korea, while I was growing up, people did not make radical changes in their careers very often and success was often defined narrowly. After my degree, I didn’t want to be in academia for various reasons. So, I worked as a management consultant but didn’t enjoy it. As luck would have it, I had to take a medical leave of absence after a minor car accident, which allowed me to take a painting class at a community college. I always dreamed of being able to paint, but never had formal training. When I started this class, I went to bed and woke up in the morning thinking about painting even though I did just some simple still-life paintings. Afterward I just had to find a way to become full-time artist.

Tell us about the evolution of your practice over the years.

I have always been interested in the representation of the female body in all visual cultures. As an immigrant, I am more aware of the contradictions in the plurality of cultures in the present American society. As a feminist, I am repulsed by the objectification of female bodies in art history and popular culture, yet I find myself strongly attracted to the sensuality of these images. This paradox led me to the imagery of food as a metaphor for the idealisation of the female body and the surrogate for the desire to consume and control. This was my first body of work after my MFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York City. As I worked on this series, I was also exploring the ethical and ecological aspects of modern food consumption by juxtaposing mass-produced industrial food with organic, homemade products. Particularly, I subverted the marketing messages of famous brands by placing their advertising slogans out of context, among highly crafted patterns rooted in older cultural traditions, to examine the impact of the proliferation of advertising imagery on our visual culture.

What were your biggest lessons and hurdles along the way?

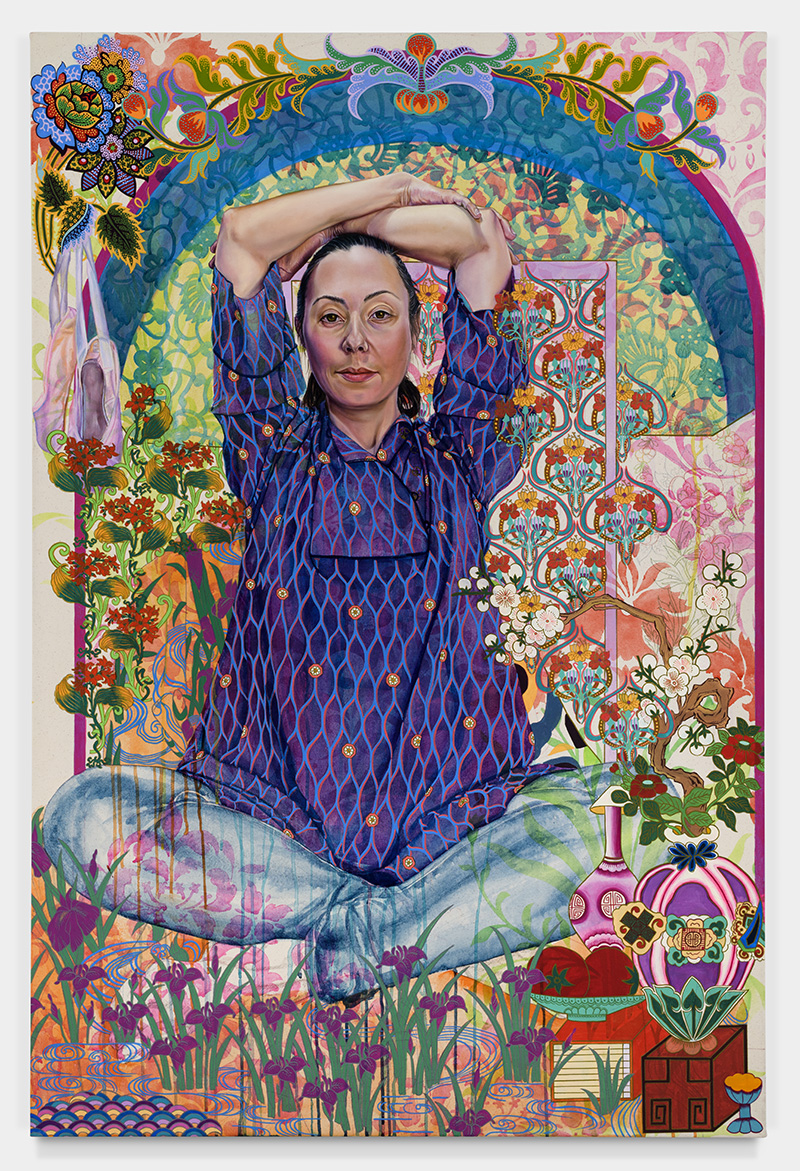

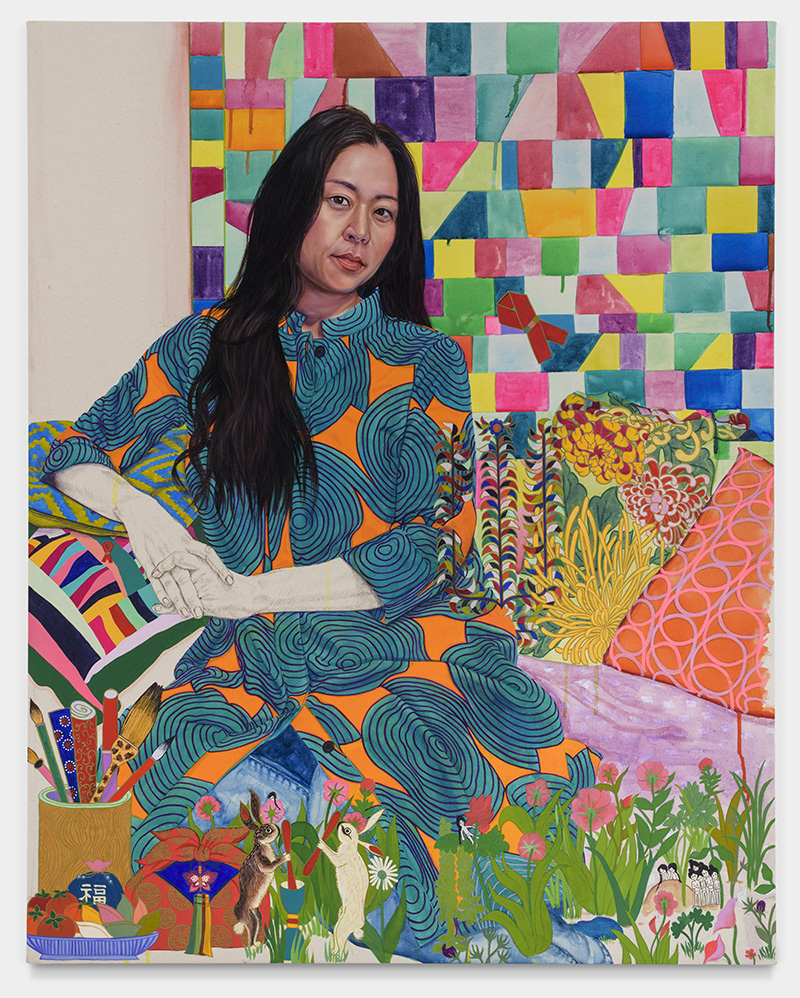

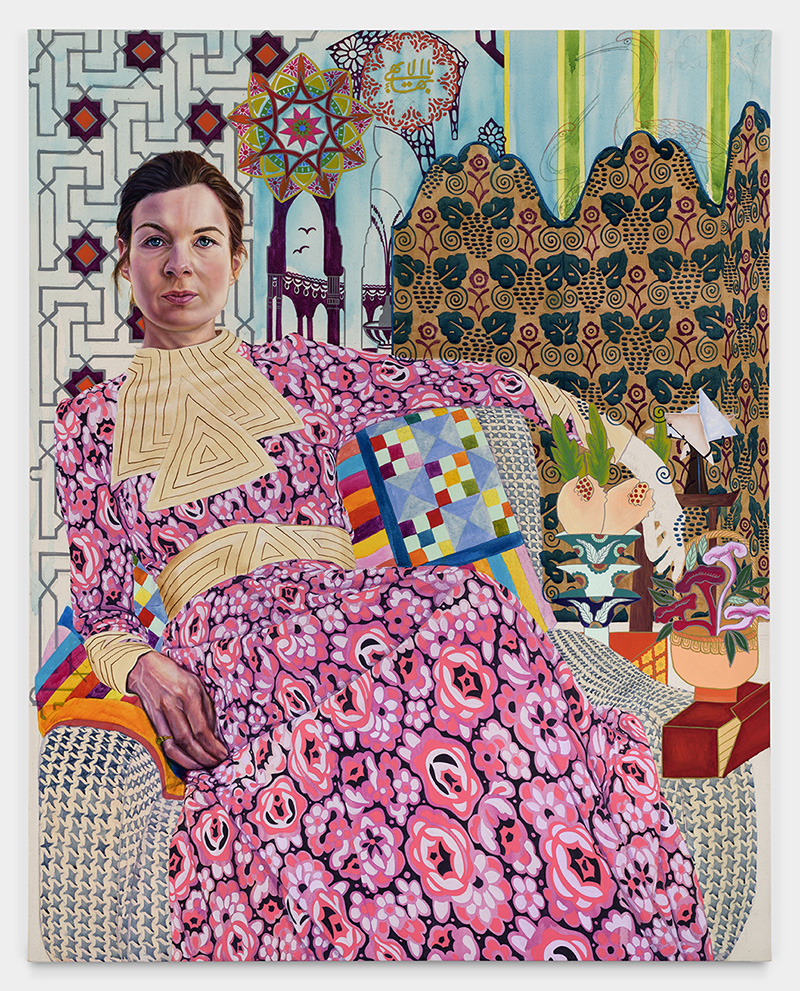

My current solo exhibition, Women in Possession of Good Fortune, at Lyons Wier Gallery in New York is a first presentation of my figurative paintings. I started painting portraits of women after the election of Donald Trump as the President of the United States in 2016. I had a difficult time focussing on art in my studio like so many other artists, especially women. But after participating in the Women’s March post his inauguration, I got inspired by the potential of collective action by women and wanted to depict that energy in the studio. I started to think about all my amazingly talented friends who engage in all kinds of creative endeavours and wanted to celebrate their gift, their “good fortune” in portraiture.

This was partly motivated by how women are portrayed in art traditionally – many portraits of men include symbols of their profession or accomplishments in the painting whereas women are portrayed just as wives or beautiful ornaments. I wanted to create portraits of women which would show their history, accomplishments and tastes. For this particular exhibition at Lyons Wier, all the women in the portraits are my close friends or acquaintances that I have admired for a long time. Feel truly blessed to be surrounded by so many women with such accomplishments, focus and diversity.

Any memorable moments?

I work from photographs and the process starts with the photoshoot. Either I invite my friends to my studio or visit theirs for a photoshoot. During the shoot, we have really interesting conversations about their cultural heritage, their hometown, food they like, etc. We also talk about their work and I ask if there is anything important that should be included in the painting.

I then expand this inquiry into a bigger cultural realm and look for patterns, icons and images with any symbolic meanings related to my subjects. It is almost an anthropological approach. By focusing on abstract patterns to give meaning, I share the feminist legacy of the Pattern and Decoration Movement from the 1970s when artists started to pay attention to the marginalisation of what was considered non-western, feminine and decorative. And my use of different media also fits into the idea of elevating traditional craft or women-oriented materials such as gouache, colored pencil and watercolour.

I also enjoy the visual richness that comes from mixing diverse materials. As for the actual composition of the painting, I don’t usually have a specific plan at the start of the painting other than the photos and some research material. I usually start with the figure in the centre of the painting and gradually build the surrounding patterns and decorative motifs, weaving the background and the foreground together. But the composition and colour choices remain spontaneous. As a matter of fact, sometimes the hardest decision to make is whether a painting is finished or not.

What inspires you? Take us through your process and continuous frameworks of reference.

The title of the current exhibition, Women in Possession of Good Fortune, is taken from the opening sentence of Jane Austen’s novel Pride and Prejudice, which goes, “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” I wanted to contrast this sentence with the contemporary condition where women do not have to marry and can gain financial independence through their own endeavours. I also wanted to highlight that good fortune does not necessarily mean financial success. At the same time, that sentence still carries a bite for many women. The pressure of balancing marriage, child-rearing and career still seems to fall heavier on women. I wanted to show how far women have come yet how far they still have to go by painting strong women.

I am inspired by Caravaggio’s dramatic composition, engagement with his contemporary society and the honesty in his characters. The Metropolitan Museum and Frick Collection is where I go to recharge myself. I always look at the works of Vermeer, Ingres and Holbein. I love the serenity of Vermeer, the suaveness of Ingres and the seriousness of Holbein. Of course,I am, hugely influenced by Matisse and Bonnard’s use of colour. I think about the empathy and the immediacy of Alice Neel’s portraits. I think about the courage, vulnerability and humour in Philip Guston’s paintings. Also count myself as a follower of the Pattern and Decoration Movement and I especially admire the work of Miriam Schapiro and Joyce Kozloff.

Recently, I saw the re-hang of the permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art and I was excited to see the multidisciplinary approach to the new gallery arrangements. I am sure I will be going back for more inspiration.

What is the primary role of an artist? How do you describe yourself in the context of challenging people’s perspectives via your work and art?

I like the term “cultural workers” as a designation for artists. I believe that artists are like canaries in coal mines, who are the first to ring an alarm whenever any socio-political injustices occur. Artists are both the mirror and the distiller of the society and culture we live in. I love the fact that you can have a broad spectrum of interests in literature, politics, society and culture as an artist and reflect that interest in your work. And you have almost direct interaction with the public.

How do you balance art and life?

It is difficult to lead a balanced life in this age of hyper-connectedness, where the distinction between professional and personal time has permanently been blurred. I also believe that life and art are inexplicably connected. When I am not facing imminent deadlines, I make no distinctions between professional engagements and personal enjoyments, and try to engage in as much cultural life as possible through literature, films, music, theatre and so on. This is possible because I don’t have any children and my partner is also very engaged in the art world. But I become singularly focussed in the studio with new projects and deadlines.

How do you deal with the conceptual difficulty and uncertainty of creating work?

I am lucky to live in New York City where there is always inspiring art to see and experience. Whenever I face roadblocks in the studio, I head out to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I like to wander around without any specific goals, to discover new areas and new pieces. Not just European collections, though I do find incredible solace in Vermeer’s A Young Woman with a Water Pitcher. Am also moved when I find everyday objects collected in the recesses of the museum corridors, like a series of rooms in the Egyptian wing with small everyday objects. Feel a connection to people who lived a few thousand years ago and empathise with their aesthetic choices and decisions.

I am lucky to live in a vibrant artistic community and have trusted friends and colleagues that I can ask for studio visits whenever I have an equivalent of a writer’s block in the studio. Also like to Google syllabi from critical theory, art history and art criticism classes from different universities. I always find an interesting topic relevant to what I am contemplating and get the material to read so I get fresh perspectives. But best answer to creative difficulties is to give permission to myself to sit quietly in the studio staring at the paintings and to write every wandering thought and feeling without any censorship.

How does your audience interact and react to your work?

Most people love the multitude of colour in my work and they usually tell me how the work makes them happy. One of the responses on my Istagram account was, “When I look at your paintings I feel all the problems of the world fade away, and I am left with looking at the complex beauty of human reality, connected to the colours of life. Your art is so uplifting and comforting.” I was really moved by this response. I also love it when a viewer lingers over my paintings to examine all the layers of details. My paintings are composed so that one can linger and find many layers.

What are you looking for when you look at other artists’ work? Who are your maestros?

I already talked about my art heroes, so I am not going into it again. In general, I am mostly moved by the intensity and the commitment of an artist’s practice. It can be conceptual, craft, technical or emotional. I am moved by some form of rigour bordering on a mania.

How does your interaction with a curator, gallery or client evolve? How do you feel about commissions?

Any professional relationship in the art world, and probably in all fields, become durable when it is based on mutual trust and respect, not on a transactional short-term perspective. I like working with people who share the same perspective and, so far, it has really worked out for me. I enjoy meeting anyone who takes art seriously. Have done a few commissions, but only for a couple of collectors who have been interested in my work since a long time and whom I would like to think of as friends.

What are you working on now? What’s coming next season?

Now that my solo exhibition at Lyons Wier Gallery in New York City has ended, I am starting to think about a new series of paintings. I am in the discussion stage with my other gallery, Kiechel Fine Art, for a solo show there. I also have an MTA New York subway commission coming up next year, and will be spending a lot of time on that project.

Before you go – you might like to browse our Artist Interviews. Interviews of artists and outliers on how to be an artist. Contemporary artists on the source of their creative inspiration.

Add Comment