Emily Graham started making pictures reflecting the feeling of her post industrial town in the middle of the country; a place where nothing ever happened.

“Honest criticism is really important as it’s hard to find people whose opinions you trust who will straight up tell you whether they think something is working or not.”

Emily Graham

Featured image: Installation view, The Blindest Man at Martin Parr Foundation, Bristol, June 2019

Emily Graham

How did your tryst with the camera begin?

I came to photography when I was a teenager – I studied art but the class was really limited, a lot of drawing fruit and learning craftwork. I picked up a camera initially to make pictures of bands and live music; at the time I was really into diy punk bands and I’d take a camera along to shows. I think I’d got some old cameras from charity shops but after a while managed to get a second hand Nikkormat from the local camera shop. A friend and I signed up to an evening class in photography at the local college, which was taught by a fairly young graduate from a nearby city. He brought in books for us to look at – Tony Ray Jones, Martin Parr, Nick Waplington, Nigel Shafran – and I was completely taken with it.

Photography seemed to be a great passport; an excuse to look, to spend time in places or with people you might not otherwise. I started wandering about the place with my camera. I’m from a post industrial town in the middle of the country, a place where it felt like nothing ever happened, so I started making pictures that were a reflection of this feeling.

My parents let me set up a darkroom on our unused table tennis table in the garage, and would spend hours there in the evenings. This isn’t to say I became a great printer – I didn’t – but the initial pleasure of and interest in photography definitely came from taking something from the world; seeing and isolating it, and then coming home to process and print, seeing it again emerge later as an image, transformed through the process of image making.

Installation view. Emily Graham. In search of the Blindest Man at Format International Photography Festival 2019

What is the primary role of an artist? How do you describe yourself in the context of challenging people’s perspectives via your work and photography?

Many years ago I went to a lecture by the experimental filmmaker Peter Kubelka where he talked about the first artistic act being the gesture of pointing, and how most of what he does is point, directing attention towards found things in the world. I really like that articulation of art, of image making. Whilst the artist can have clear intentions for their work, and for how it is seen, what happens next is in the hands (or eyes) of the viewer….that’s part of the exciting thing about putting work out into the world, you can’t control the readings of the work. Photography is such a slippery medium, it’s near impossible for images on their own to have fixed meanings, and that’s part of the attraction for me.

The work that I make often deals with elusive subject matters – and the work comes together in the editing – so I hope that the images captivate enough for viewers to spend time with the work, to have a reaction to the work – whether that’s emotional or intellectual.

How do you deal with the conceptual difficulty and uncertainty of creating new work?

I make work through a process of getting out and shooting, reading, examining, editing etc. When I’m not sure what I’m doing, I go out and walk with my camera – either I get on a train or go in the car somewhere, preferably somewhere I don’t know so I can just wander. Recently with the restrictions due to C-19, I’ve been walking around my locality much more than I ever have. For me, this is a helpful process not only for making pictures, but for thinking, and making sense of what I’ve been thinking about. Often the walking and looking is more valuable than the resulting pictures.

I often have a few different threads that I’m thinking about at once, and I try to hold onto, follow, make pictures with those in mind, and see where they go.

Emily Graham

Installation view. Emily Graham. In search of the Blindest Man at Format International Photography Festival 2019

Tell us about your studio, what kind of place is it?

I mostly work out and about with my camera, so my working studio is a simple space, where I research, scan, and edit. I have different folders or boxes for different strands of research / different projects. Alongside my own practice I also work with photography in a project management and curatorial capacity, so I like to keep things clearly separated.

Could you describe your usual work-day in the studio?

When I’m in the studio I like to get a full day in so I’ll start early, perhaps going for a walk with my camera first thing, in the summer at around 7.30am. I’ll often then spend time at my desk working with different images, prepping images for print, looking at different images on the large monitor next to each other to start to group pictures. What I do on a daily basis depends where I am in a project – at the moment I’m trying to finalise a book dummy, so I’m often chipping away at that on indesign or by working with previous dummies that I’ve made – cutting, moving things around, annotating, and I’m working on something new, so research; finding locations to walk, finding people to work with, getting access, preparing for visits…that takes a lot of time.

If I’m researching, I will often have the scanner running in the background (if I have new pictures to scan, that is). There are often small sets of prints pinned to the wall, so that I can keep looking at pictures and work out what works and what doesn’t.

At the moment I have a nine month old so an entire day in my studio isn’t possible, so I’m learning to adapt to working in smaller bursts!

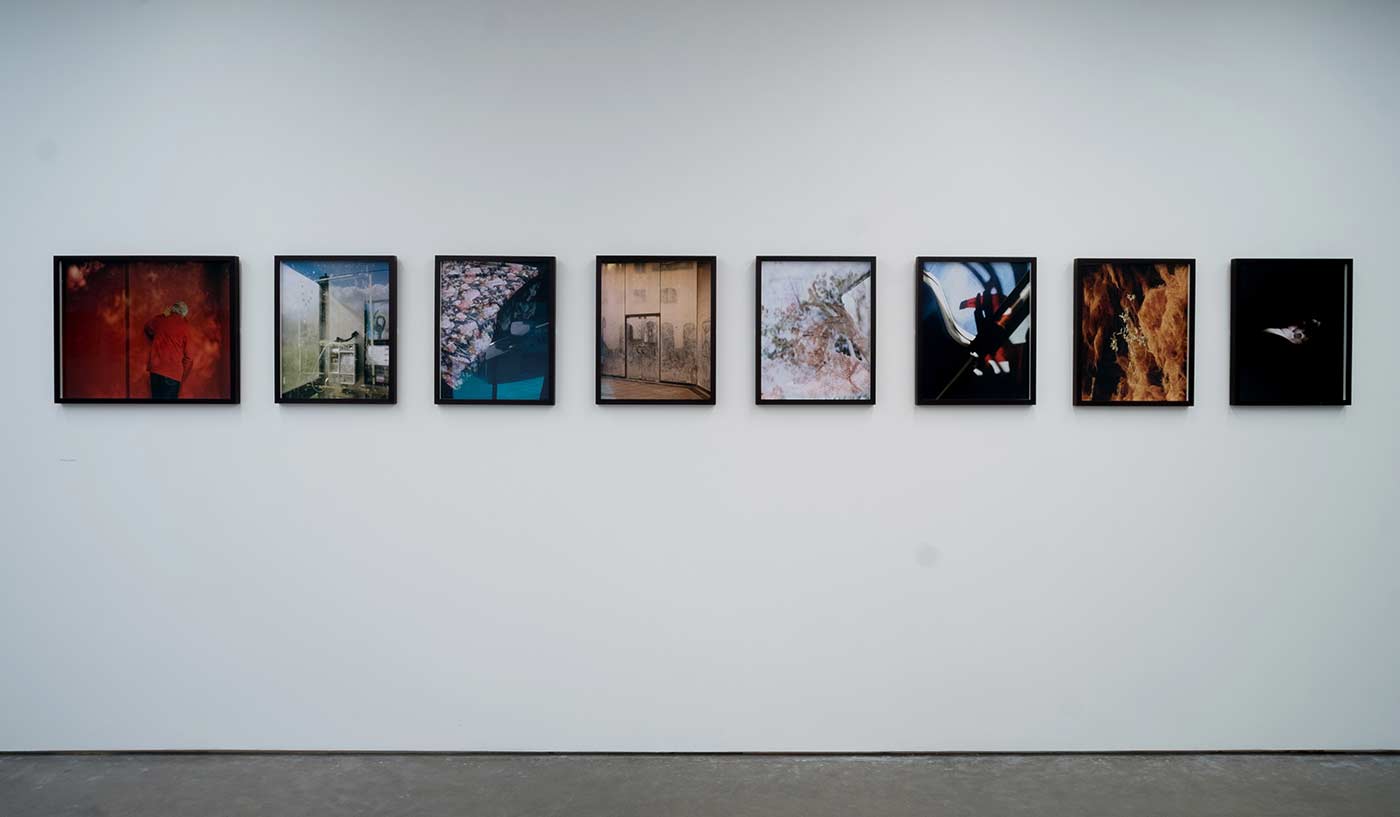

In the pictures from The Blindest Man, I was trying to create a sense of strangeness, of an in-between time, neither dark or light, day nor night, with the colour pictures.

Emily Graham

How do your audience and the market interact and react to your work. What is that one thing you wished people would ask you but never do?

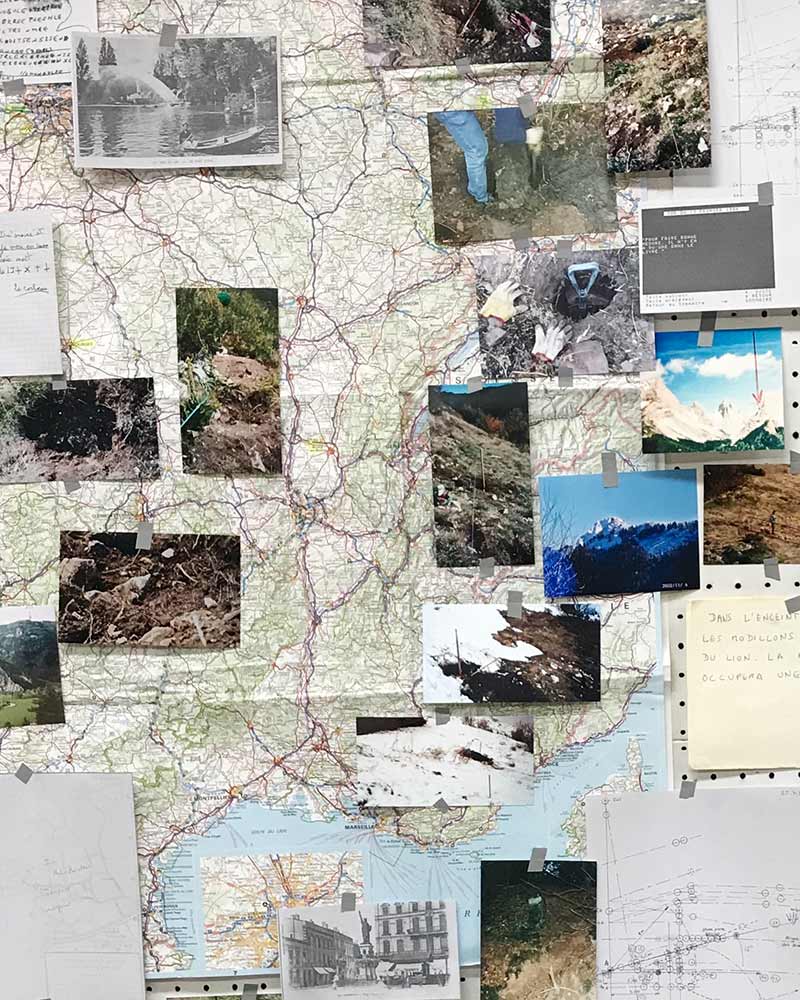

I’m not sure what I can say about the market but there’s been a lot of interest in my last body of work: The Blindest Man. The open ended work follows the story of an unsolved treasure hunt to reflect on the act of searching, for specific outcomes, for dreams, for meaning etc, and I wanted to use it to also think about the act of photography, of chasing an image, of images as documents being elusive in themselves.

Working with colour photography is something I think about a lot, now that photographs are in colour, it’s taken for granted. A lot of contemporary artists are going back to working in black and white. Colour pictures are difficult, it may be an obvious thing to say but colour and light really affect the formal qualities of a work, the mood of a work, how an eye moves over a picture. In the pictures from The Blindest Man, I was trying to create a sense of strangeness, of an in-between time, neither dark or light, day nor night, with the colour pictures.

Detail view. Emily Graham. In search of the Blindest Man at Format International Photography Festival 2019

I really love seeing work in non-traditional spaces.

Emily Graham

What are you looking for while viewing photography?

Really simply, images that compel or excite me. That make me feel something.

In terms of work that has shaped my experience, books are my go to. Volker Heinze’s Ahnung, is a book of colour photographs made in the late 1980s, when the Berlin Wall was still up. The book is not so much about documenting Berlin at that time, as about a state of mind; of living in a walled city. The book is full of hazy details, pictures that are dark with shallow depth of field, and is a masterpiece of colour photography. It showed me how colour photographs can reflect or evoke feelings rather than simply documenting the appearance of things. In the text with the work he talks about the unique quality of photography being the relationship between the image and its former reality, and how photography makes sense of that relationship. I’m really interested in that idea.

Which shows, performances and experiences have shaped your own creative process? Who are your maestros?

First discovering Palais de Toyko in Paris was pretty memorable, it blew open my understanding of what a gallery or museum space to be. The first exhibition I recall seeing there was Wolfgang Tillmans, where prints were simply tacked to the enormous span of wall space in PT. So many other subsequent exhibitions have blown me away; Hiroshi Sugimoto, Laure Provost, John Giorno to name a few. I’ve got a lot from seeing how different curators or artists use that space in different ways.

I really love seeing work in non-traditional spaces. When I first moved to London, I saw a Christoph Büchel exhibition in a warehouse in East London, in which he’d created a huge immersive installation comprising a labyrinth of rooms and spaces to move through and discover claustrophobic spaces and abrasive noises. The work felt dark and strange but the experience really stuck with me. ArtAngel continuously make incredible installations; Taryn Simon’s An Occupation of Loss, and Ben Rivers at the old BBC Television Centre were both amazing.

Emily Graham, with Installation view, The Blindest Man at Martin Parr Foundation, Bristol, June 2019

What is your experience of the power of formative collaborations?

After I first graduated I set up the Contact Collective with a few friends, later called Editions, and later still Night Contact. The initial aim was to just meet up and talk about our work, and collectively write a blog on photography. Soon this expanded to running community events, to more formal critiques with photography professionals that were open to all, and slideshow events, which eventually morphed into a festival that we ran in London and Brighton for a couple of years. I ran this primarily with Anna Stevens, who lectures at LCC, and runs the multimedia team at Panos Photos, and a group of other photographers.

We all got a lot of energy and ideas from the group dynamic. It’s much easier to achieve ambitious things when there’s a group working at it! I’ve always found that a good peer group is really important, not just for critical feedback and support, but also for having others around you who are on a similar path. My friend and fellow photographer Hin Chua has also been someone that consistently challenges, criticises, and supports. Honest criticism is really important as it’s hard to find people whose opinions you trust who will straight up tell you whether they think something is working or not.

In terms of education, I completed the MA programme at UWE last year, where Aaron Schuman leads the course. Aaron also taught on my BA, and is a completely amazing educator, he helped me figure out a process for keeping my practice moving going forward, and pushed me to get my work out into the world, for which I’m very grateful.

Please mention any residency, curator or gallery that helped you along on your artistic journey?

More recently I’ve really enjoyed working with an editor, Charlie Hall, who commissioned me for the Wellcome Trust’s editorial outlet, Mosaic, and further to the initial editorial feature I’ve developed the work, and will show it later this year at Landskrona Foto in Sweden. Whilst Charlie developed the idea for the shoot with me, she also gave me a huge amount of freedom whilst I was on location. It’s rare that you get the opportunity for really interesting editorial assignments, rarer still that you get freedom to make pictures that you want to make whilst on said assignment. The work is about memory, language, and communication – based around a very real problem of how we communicate with future generations about dangerous nuclear waste.

Nuclear waste is being stored by burial in deep underground sites, and the most dangerous remains for up to a million years. The problem with this, is how we communicate with future generations about this – if current language is lost, without inciting curiosity. It’s fascinating to try and think about this kind of time scale, and to think about the materials of memory, what lasts over time, and what can be communicated outside of language? Is it possible to create an eternal memory culture around a burial site? And then, in terms of photography, can you have a visual language that can communicate free of words? A really fascinating thing to think on and in terms of visual representation, it’s in line with some of the concerns of previous work I’d made.

Installation view, Emily Graham. The Blindest Man at Martin Parr Foundation, Bristol, June 2019

What was your first sale? Do you handle the commercials yourself or is it outsourced to a gallery/agents?

I sell my work through different outlets, sometimes directly and sometimes through dealers.

What are you working on now? What’s coming next season?

I’m currently on maternity leave but during this time I have been making photographs closer to home.

Before Covid19, I was beginning work on a commission for GRAIN, an arts organisation based in Birmingham, to make work in the rural Midlands. I’ll be making work in my home town, which is loosely about the body in external space but I’m just now thinking about how the project will change in response to the changes brought by the pandemic.

I’m showing some new work at Landskrona Foto Festival in Sweden in September, as part of their Architecture of Memory programme. There’s also a feature on The Blindest Man coming out in the next print edition of Splash and Grab magazine.

For enquiries contact: emily [at] emilygraham [dot] co

Before you go – you might like to browse the Asian Curator curatorial archives . Contemporary art curators and international gallerists define their curatorial policies and share stories and insights about the inner runnings of the contemporary art world.

Add Comment