I create work that speaks about the female body in quite a direct way which inserts the work into this bracket of feminist art – and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that.

Contemporary artist Camilla Hanney

Artist interview

London based contemporary artist Camilla Hanney talks about exploring and questioning notions of embodiment in her work, in an interview with Anjali Singh for the Asian Curator

How to become an artist.

Please tell us a little about yourself. How do you describe yourself in the context of challenging people’s perspectives via your work?

I’m originally from Ireland where I studied Visual Arts Practice at undergraduate level. I came to London about 3 years ago to do an MFA at Goldsmiths University, from where I graduated just over a year ago. I work mainly through ceramics, sculpture and installation and my practice explores issues surrounding time, gender, tradition and the corporeal, often referencing the body in both humorous and challenging ways.

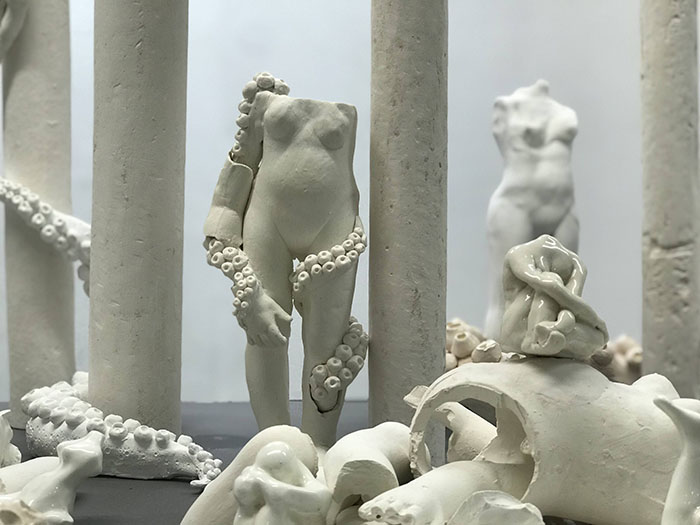

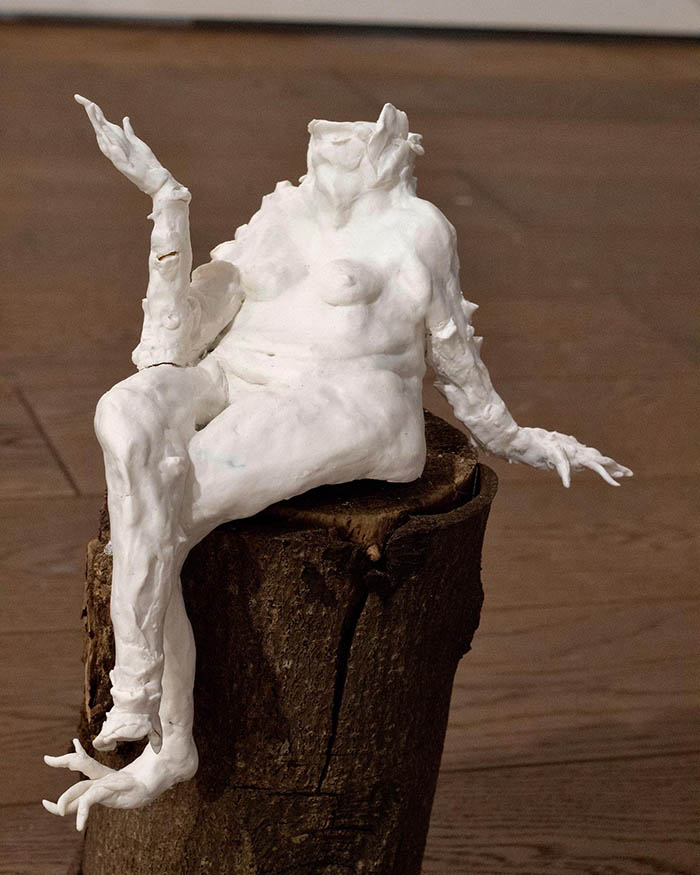

In much of my work I use history and allegorical references as a means of exploring and questioning notions of embodiment – how bodies are controlled and regulated, what causes us to feel shame towards our bodies or feel afraid of them? And why are some more vulnerable than others? I often create hybrid, sculptural compositions of the figure merged with animals, domestic objects and aspects of the natural world to discuss and challenge issues concerning the borders and boundaries that have been placed onto our bodies to conceal its impurities. Society has conditioned us to believe our bodies must exist within the boundaries of culture to prevent them from returning back to their natural, primal state. I’m interested in challenging this notion.

What brought you to the world of contemporary digital/visual art and how did you start?

Initially I wanted to study textiles. I realise now that I am definitely not a designer. I did a year-long portfolio course after leaving school so that I could apply for art college, and this was probably where I really began to learn about contemporary art. At school I don’t think I ever really felt there was a subject I excelled in, finding art was like discovering a second language, an entirely new way of communicating through texture, materials and imagery that allowed me to form a dialogue with the people who viewed my work . I then did a BA in Ireland where I specialised in sculpture, and later continued my studies on the Masters of Fine Art Programme at Goldsmiths University in London.

Lets talk about your frameworks, references and creative process.

My work tends to focus on the female body and its representation because it is the framework that best describes the body I inhabit. But I’m also very interested in the malleability of the body and it’s social constructions, the fluidity of gender and the destruction of former representations of women that have been portrayed through art, myth and religion.

I tend to subvert quite traditional, genteel crafts in my work and I do this as an attempt to transgress and also contemplate conventional modes of femininity.

What would you call your style?

I’m not sure if my practice has its own style but there is usually a sense of antiquity or times gone by in my work, that occurs in both the materials and references I choose to employ. I suppose I use this as an entry into discourse around the archive and forgotten or lost histories.

Choice of medium in art

Let’s talk about the evolution of your practice and medium of art over the years.

At the beginning of my practice I was using quite humble materials, often organic matter sourced directly from nature. At that stage my practice mainly focused on Irish women’s stories taken directly from the archive. I would use my practice to resurface women’s histories ; and at times portray them under a different light. I used to accompany my work with archival texts relating to these histories. I worried that this was a very pedantic way of disseminating the work and only spoke of issues that were attached to a very particular collection of women. Now, I try to create work that is more universal in its intent, that can be perceived in more ways than one and can describe both the pain and pleasure of being a body.

Tell us about your commitment to your current medium in art.

Materials are an integral component in my practice and I spend a great deal of time investigating ways to transform them, projecting new identities and layers of meaning into my work in doing so. Recently, ceramics have heavily informed my work. I find the malleable properties of clay provide me with the freedom of form to describe the body in fantastical ways. Porcelain in particular has become a medium I often choose to work in. Its material properties convey an awareness of opposing states, appearing to be not only heavy, solid and strong but also light, fragmentary and soft, demonstrating both strength and vulnerability. There is a sense of purity and innocence found in porcelain as a material that I attempt to subvert through my practice. Similarly I often incorporate white lace into my work.

The creative process: creative blocks

What does the creative process mean to you?

I have quite a tactile approach to art making and always work directly from the material. I rarely create work with a vision of the finished piece in mind – it’s those happy accidents that occur along the way that often shape the work I make. I’ve shattered and broken works by accident and then presented them that way because I’ve found them more interesting. Casting is a process I use quite often. I think this is partly because I love that it’s a method that’s also used in things like archeology and is essentially a tool for recording traces of the past. I also feel there is a certain level of catharsis existing in the ritual of my own practice that keeps me stimulated (and sane!) when times are strange and uncertain.

How do you deal with the conceptual difficulty and uncertainty of creating new work

When I’m having conceptual difficulties I allow the material to lead the work. It usually takes me to a place of subconscious thought, eventually revealing why I chose to work in a certain way and what I’m trying to express.

How do you overcome creative blocks?

By channelling my attention elsewhere for short bursts of time. Sometimes when I spend all day looking at my work it just stops making sense and then I know it’s time to take a walk and come back with a fresh pair of eyes. If I feel as though I’m really stuck in my practice or am having an artistic block I go to galleries or, even better, I go to museums. I spend a day wandering through the Natural History museum or the Wellcome Trust’s permanent collection and suddenly I start to feel inspired again. I read, go online; take a field trip.

Society has conditioned us to believe our bodies must exist within the boundaries of culture to prevent them from returning back to their natural, primal state. I’m interested in challenging this notion.

Contemporary artist Camilla Hanney

The creative process: creative inspiration

What is your source of creative inspiration?

I often look at religion, alongside society, as a contributor to the ways in which historically women have been contained, confined and reformed of their passions and perversions, ultimately leading to the formation of the idolised, passive female. Often my work both embodies and mocks age old ideas around female lust as being hideous and corrupting. I feel certain aspects of womanhood are actually quite grotesque and this doesn’t need to be concealed. I make work that best relates to the body I inhabit and at times addresses the stories of a generation of Irish women that came before me. That work I make is not self-confessional artwork, but at the same time the work is part of my identity which I feel provides me with agency to discuss these issues.

What are you looking for in other visual artists work?

I think I’m naturally drawn to work that is open, honest and easily accessible. Prefer art that shows emotion but is not ‘preachy’ in its execution, I tend to prefer art that is presented in an ambivalent way and allows the viewer to take away from it what they please. I also appreciate work that reveals an artist’s time and labour, it helps me to believe they have a lot of care for their practice.

Which shows, performances and experiences have shaped your own creative process? Who are your favourite contemporary artist maestros?

I revisited Rachel Kneebone’s site specific installation ‘399 days’ several times while it was on display in the V&A museum last year. The installation is a large scale porcelain tower of seething flesh and limbs. It’s rare to find a work that can be delicate and monumental all at once, her work really did create a sense of awe for me. I was also very taken by Columbian artist Doris Salcedo’s exhibition at the White Cube Bermondsey. Her dedication to the tales of the Columbian archive is quite inspiring and the manner in which she can convey tragic tales of Columbian violence through poetic installations is both beautiful and terrifying, providing viewers with an understanding of the politics of ‘the trace’. Dorothy Cross would have to be my favourite artist. I adore her clever use of materials and her commitment to dealing with themes that discuss our relationship to the natural world. Other artists I find inspiring include Louise Bourgeois, Anselm Kiefer, Mark Dion and Kiki Smith.

Mention any art books, writers or blogs of note

I often turn to fiction for influence. I was really taken by the Korean author, Han Kang’s book, ‘The Vegetarian’. The short novel uses a somewhat ecofeminist approach to unravel a story relating to the exploitation of women and nature by considering both as objects. The hybrid imagery of woman and plant that appears throughout the story has definitely influenced aspects of my work. Similarly, the eroticism and grotesque imagery of Angela Carter’s subversive fairy tales has informed my work at times.

I also read a lot of Irish writing. I’m a huge fan of Sinead Gleeson’s ‘Constellations: Reflections from Life’, a compilation of intimate essays that discuss myriad issues relating to the human body. From illness to reproductive rights. Eimear McBride’s ‘A Girl is a Half formed Thing’ also had a huge impact on me when I read it and even more so when I saw the text performed as part of the Dublin Theatre Festival. I admire McBride’s very direct approach to handling the vulnerability, violence and power dynamics of female sexuality as portrayed through her main character.

Similarly, I was very moved by Lisa Taddeo’s book ‘Three Women’ which uses three diverse women’s stories to unfold the incredibly complex nature of female sexual desire.

Most recently I’ve been reading ‘Girl. Woman. Other’ by Bernadine Evaristo which has a wonderfully contemporary take on feminist issues that highlight the importance of intersectionality through twelve intertwining narratives.

On contemporary digital/visual art.

What does contemporary digital/visual art mean to you? What role do contemporary artists play in shaping culture and society?

I feel it’s important to create work that informs viewers that agency is required in the present by confronting them with stories of the past or, in other words, to create art that challenges the act of forgetting. It would be tempting to believe that art can redeem the past. It can’t. However, it can reveal. An artist has the unique ability to challenge the formalities of the archive as we know it and transform it into a more morally complex, visceral repository, obscuring and blurring the lines between fact and fiction, that usually rigidly encase our understanding of the archive and its purpose. I feel it is important to fill in the gaps and silences of women’s histories to provide the formerly silenced and oppressed with a voice.

Career as an artist

Let’s talk about your career as an artist, or if you prefer artistic journey. What were your biggest learning and hiccups along the way?

I think realising that all artists experience as much, if not more, rejection as they do success, and being able to pick myself up and stay motivated during moments of doubt has been my biggest learning. Experiencing failure has been important for my own self growth as an artist and forming a tough skin.

Describe a professional risk that you took. What helped you take it?

Choosing to speak about the female body and the issues that surround it in my practice can be viewed as a professional risk. I never want to delve too deep into the social and political issues that present themselves in my work; but similar to most artists they are definitely there like it or not – I think all art is political in some respect.

I create work that speaks about the female body in quite a direct way which inserts the work into this bracket of feminist art – and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that. Though I don’t reject that title being placed on it, but really I make work that best discusses the body that I inhabit which is the body of a woman, an Irish woman. It’s in no way self confessional art and doesn’t really speak directly about lived experiences, but If I’m presenting an argument or making a strong statement in my work I actually like to try and keep it a little bit open ended most of the time. I never want to bombard people with my opinions, I think it’s more interesting to allow viewers to find something in the work that speaks to them, and if it’s not the message I intended I don’t think that’s necessarily always such a bad thing.

Any mentor, curator or gallerist who deserves a special mention for furthering your career as an artist?

I was fortunate enough to receive a studio bursary from Sarabande in conjunction with New Contemporaries which has provided me with a studio for a year. As a graduate, fresh to the London art scene, I felt Sarabande offered a safety net, granting me time and space to continue my practice in a supportive environment.

Best piece of art advice, and who was it from?

I remember before I left my undergraduate degree one of my lecturers gave a ‘life after graduation’ talk. They told us not to continue our studies abroad unless it was in a city we could see ourselves spending at least the next 5 years in. I think that advice played quite a crucial role in my decision to study and remain in London.

Lets talk about the importance of a peer artist network & art advice.

I feel very fortunate to have left Goldsmiths with a strong peer network. As I will always have other artists I can turn to for advice or even just bounce ideas off every now and again. I think artists often grapple with moments of self doubt in their practice, it comes with the territory. Because of this I feel it’s very important to have access to a community of creatively minded people that can see you through those times of uncertainty.

Is it imperative to have a visual art degree become a visual artist?

It’s definitely not essential to have an art degree to become an artist and plenty of creatives have established successful careers without any formal education. But I do feel having a degree helps. Art college provided me with a safe space to receive criticism and experiment with my practice, it was where I really refined and developed my practice and it’s core concerns.

On artist commissions

Are you more of a studio artist or naturally collaborative by nature?

As my practice involves quite laborious, time consuming processes I tend to work in a very isolated way, often spending long hours alone in my studio. However, I do still enjoy the challenge of working in collaboration. I think it’s always important to be open to learning from others and forming new relationships.

Art marketing & building an audience

Does art marketing come naturally to you?

No, definitely not! I’ve been lucky enough to receive help and support in art marketing over the past year through curators and mentors. I think there is a lack of practical skills taught to art students that can create difficulties in this area and can ultimately lead to the underselling of work. Hopefully in time this will change.

Do you handle art valuation and sales yourself?

Occasionally I sell work privately to art collectors who have contacted me directly, but generally any sales I have made have been organised through galleries I’ve exhibited with and the prices, commission charge etc. have been agreed on in advance.

On upcoming work

Themes you are currently working on?

I made a three tiered porcelain cake while I was confined in my home during lockdown, its surface glistening with gold and pearlescent glaze, its precarious stance resembling a gluttonous leaning Tower of Pisa, ready to keel over under the weight of its own decadence. A sculpted mouth presented itself beneath the top layer of icing, appearing as though seconds away from sugar induced suffocation, but the facial expression is nonchalant, bored, unsatisfied.

In this turn of events the fondant feasts on the figure as if attempting to consume and stifle the body’s urges and temptations in a struggle to contain its dangerous, immodest overspills.

Long hours spent working in a domestic space during lockdown caused me to reflect and contemplate the bodies that have been bound and confined to household rituals. The domestic sphere, in particular the kitchen, holds an expansive history as a site of submission for women and minorities, and bears a close connection with women’s traditional role as docile caregivers. Cinema, folklore and fairytale have opened our eyes to the subversiveness and monstrosity of women in association with food preparation. Poisoned apples, cauldrons and meat cleavers have transformed the role of housewife or kitchen maid into temptress, wild woman and witch, in many ways providing agency or an escape from the compliant wife or kitchen maid.

I hope to continue exploring ideas of excess and desire. The material significance of fusing culinary processes with ceramics has urged me to question and examine the instability of human wants, our insatiable tendencies and carnal pleasures that often straddle the borders between desire and disgust.

Any upcoming show or events we can look forward to ?

I have some work being exhibited at ‘House of Bandits’, a takeover event which is currently on display in Burberry’s former retail space in Mayfair. The pop up exhibition features the work of both artists and designers, and is scheduled to run up until Christmas. I will also be exhibiting work at Muse gallery in an upcoming exhibition featuring the work of 10 emerging artists. The show will run from the 9th-22nd November. I am also going to be included in an online charity exhibition next month curated by Charlie Siddick that will be raising money for the LGBTQ+ community. The dates for this are yet to be confirmed.

Artist Contact

Email: camillahanney@gmail.com

Before you go – you might like to browse our Artist Interviews. Interviews of artists and outliers on how to be an artist. Contemporary artists on the source of their creative inspiration.

Add Comment