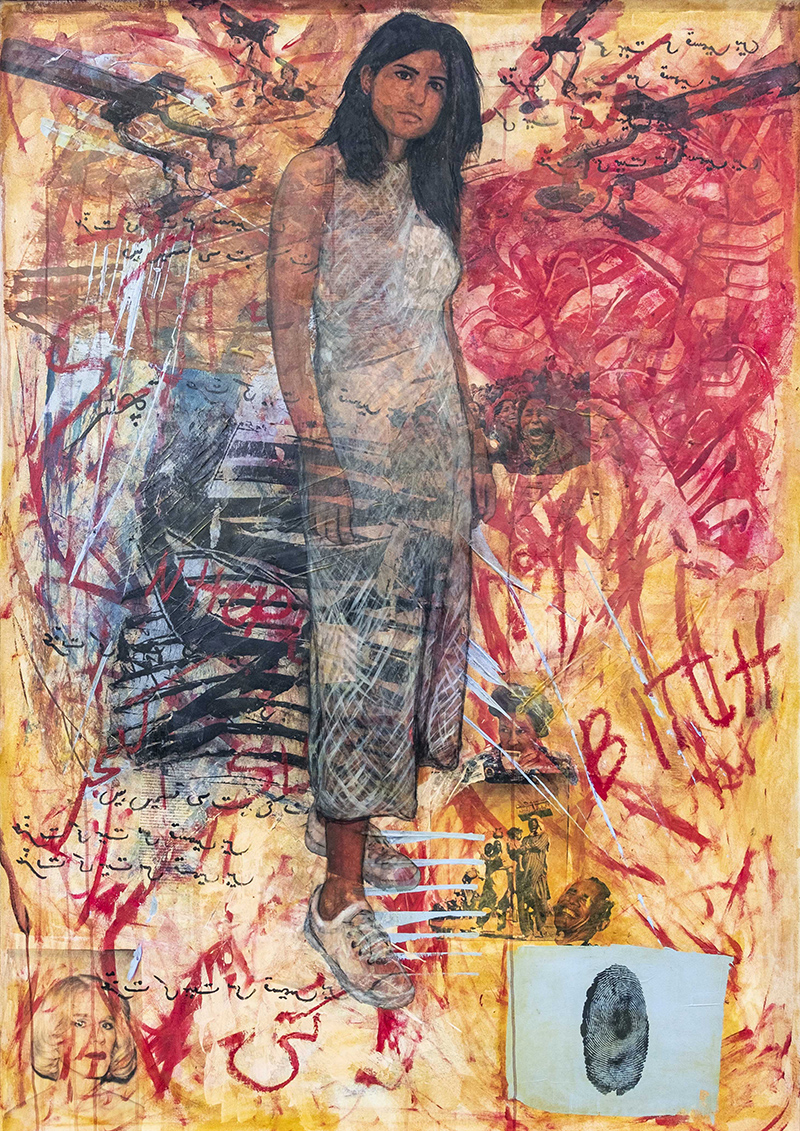

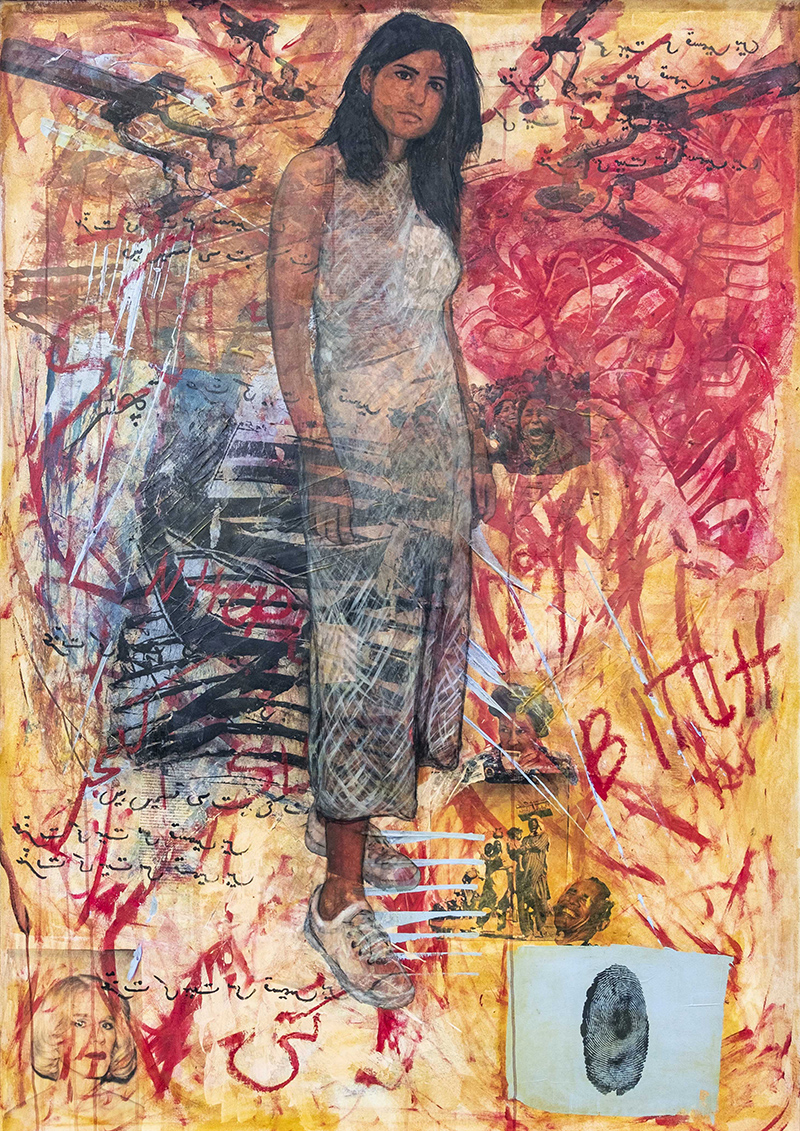

I have found that the audience finds my work uncomfortable. At times it’s seen as visually overloaded, too sad, or too bold, or too loud. I used to think this was a problem, but now that I have a greater understanding of my work, I have come to realise that I am doing something right if they are uncomfortable and awkward around it.

The unforgiving nature of glue, the rush of performance and the challenges of the South Asian woman lie at the heart of Amber Arifeen’s body of work

How did your tryst with art begin?

My journey into the arts has been different to most and began a little later in life. I actually never thought of pursuing art as a young girl, even though I was always making art, so much so that all my room walls were covered with glass sculptures and paper installations. When I was 17, I went on to pursue studies and a career in international development, thinking I would one day help change things in Pakistan. After completing my MBA, I began working for an NGO in Karachi.

This was a period of many realisations and frustrations, including the realisation that the development sector was tangled up in a number of bureaucratic and political challenges, burning millions of tax payer dollars but not leading to sustainable impact, and I, essentially, was just another cog in the wheel. It was a hard truth to face. Continuing this career path, something I worked my entire life for, meant that I would have to betray myself in many ways. Somehow this one simple realisation brought to surface many repressed fears and doubts. During this time of introspection, I began to question everything, starting with why I made certain choices, such as ignoring my talent and interest in art, and leading to larger, more philosophical questions having to do with what constituted the South Asian female self. It was during this time that I picked up painting again.

What is the primary role of an artist? How do you describe yourself in the context of challenging people’s perspectives via your work and art?

I think every artist decides for themselves what this role might look like. As humans we are all trying to make sense of our place in this world, ourselves, and our environments. By creating art, artists are essentially addressing gaps in this process, to reach a greater understanding of ourselves. We’re often been labeled as critics, but I believe we fulfill a much larger and more important role than that, which is that of introspection and reflection. In my own work, it is important for me to be bold and honest in this regard. I see the world from this lens of introspection, and so the ideas I grapple with are becoming bolder as I dig deeper, challenging what we know of the world and encouraging the audience to shift perspective.

Let’s talk about the evolution of your practice. Tell us about your commitment to your current medium.

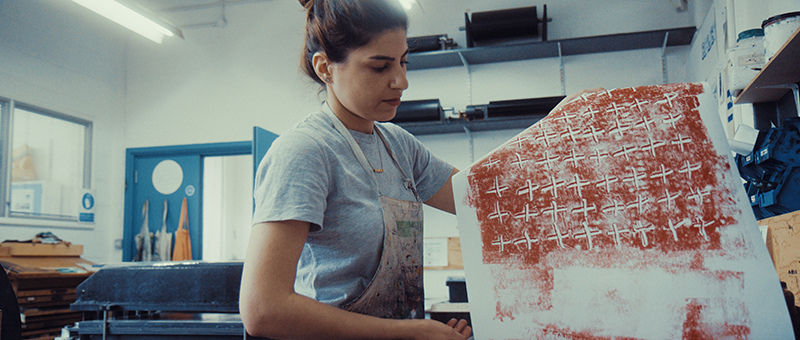

Although I began painting with oils, the medium I most frequently use now is actually glue. There is a theatrical element in my work. I use a combination of collage, images, printing techniques, and paints to construct my paintings. There are lot of processes and movements I work with, and physically, I feel like I am building something. Glue somehow allows me to do that. Historically, glue was made from bones and sap from trees, elements that held life forms together. So, in a way, when I construct my paintings using glue it’s almost as if I am bringing something to life and producing a kind of subjectivity for the Asian woman that I am most interested in.

Given the evolution of my performative painting practice, it was only natural that I move into performance. Performance has opened new doors for me, emotionally and professionally. I have found that it is in performance that I am able to express the things that I find hard to explain or articulate. An experience I am unable to communicate to others through painting or language, I am able to evoke in the audience through performance.

What inspires you? Take us through your process and continuous frameworks of reference.

My process is highly intuitive early on, followed by a research and fact-finding mission. All of my inspiration stems from a lived experience – so if there is an event or a news report, or there is an encounter with an image, piece of literature or a play that stirs in me an experience of discomfort, I sit in that experience for a while after which I begin to collect references and research to contextualise that experience. I am only beginning to understand that this is my process. For a while I didn’t know I was following this structure, but as I make more work it has become clearer to me.

Lets talk about your artistic journey. What were your biggest lesson and challenge? Which is the most memorable moment?

I think for me the biggest challenge was that I never thought I was going to be making art professionally. The change in career, and the thought that I had to catch up on so much and, in a manner, restart life again was the most frustrating part of it. I had to overcome a lot of fears to take this bold step. When you make big decisions like that, it requires deep introspection. Most people sail through life, unconsciously. I don’t think I was living with intention before this. So when I look back now, I am so glad that it happened this way. While it was a rude awakening it was also a great learning experience for me, personally and professionally.

The most memorable moment and, possibly the biggest learning moment, was when I performed with Amin Gulgee in Paris earlier this year. Amin invited me to participate in a group performance show he was curating and gave me the autonomy to do what I felt like. At first, I thought I can’t do this. I just wish he would tell me what to do. I had acted in plays as a young girl in school, but this was something entirely different. I actually didn’t know where to begin but I thought I have to be brave and just do it. And so, it was the first time that I pushed my practice and challenged myself artistically – opening up the question as to how I could transfer my ideas from painting into performance. It was really difficult and frustrating initially, but it taught to me so many things about a process that works for me. I eventually came up with a performance piece called De’voilez, which was in response to the city of Paris. I used the same logic and thinking process as with my paintings and applied them to the performance piece, drawing inspiration from a lived experience of discomfort caused by an event, that of the French ban on the niqab, and contextualising it using historical and contemporary narratives.

It was only during the performance when I was completely transported into the experience that I was meant to demonstrate. I truly understood the power of performance then. That was a huge moment for me.

How do you deal with the conceptual difficulty and uncertainty of creating work?

I used to get frustrated with this aspect, but over time I have learnt to embrace the timely and often painful process of developing an idea or concept. It’s literally a gestation period, where I’m sitting thinking about these ideas, stressing out, working out solutions, and when that runs its course, I somehow have something concrete to work with. This also allows me the freedom to work through ideas that are shifting and changing. While this may not work for everyone, it seems to work for me. I thrive on uncertainty. Again, it is part of my process. I can never know how my work will turn out because it’s all intuitive – particularly when it comes to painting. I work with glue, a material that can’t be undone. I can build over it, but I can’t undo what’s been pasted.

How does your audience interact and react to your work?

I have found that the audience finds my work uncomfortable. At times it’s seen as visually overloaded, too sad, or too bold, or too loud. I used to think this was a problem, but now that I have a greater understanding of my work, I have come to realise that I am doing something right if they are uncomfortable and awkward around it. All my work is inspired from moments of discomfort, chaos, and confusion. As South Asian women, moments of discomfort are met with a multitude of thoughts, fears, and contradictions that can often consume us, without us realising it. We carry huge burdens and I suppose that’s what comes across in the work.

What are you looking for when you look at other artists’ work? Who are your maestros?

When looking at other artists’ work, I am almost always looking at the process. The process tells me how the artist thinks. I think through process myself, rather than through drawing or narratives. Most of the artists I look up to have all played with their surfaces, processes and materials in some form or the other. Usually there isn’t a single narrative in the work, but a disjointed set of themes which can at times come off as confusing. Robert Rauschenberg has been a huge influence on me in this regard. I recently saw an exhibition of his at Ropac Gallery in London, and it allowed for a huge shift in my practice. I was moving through this work in way that I hadn’t experienced before. Some other artists who I look up to include Mickalene Thomas, Shazia Sikander, David Wojnarowicz, and Claudette Johnson.

Add Comment