Contemporary artist Monique Lacey crushes the male-centric narrative of Minimalism, literally.

There is nothing worse than walking past an artwork and thinking “meh”. I want to feel something; the work has to hold me. I look at art from the perspective of being a maker, so I’m looking for the process of the making to be present in the work, but not in a way that seems so obvious as to how it got there..

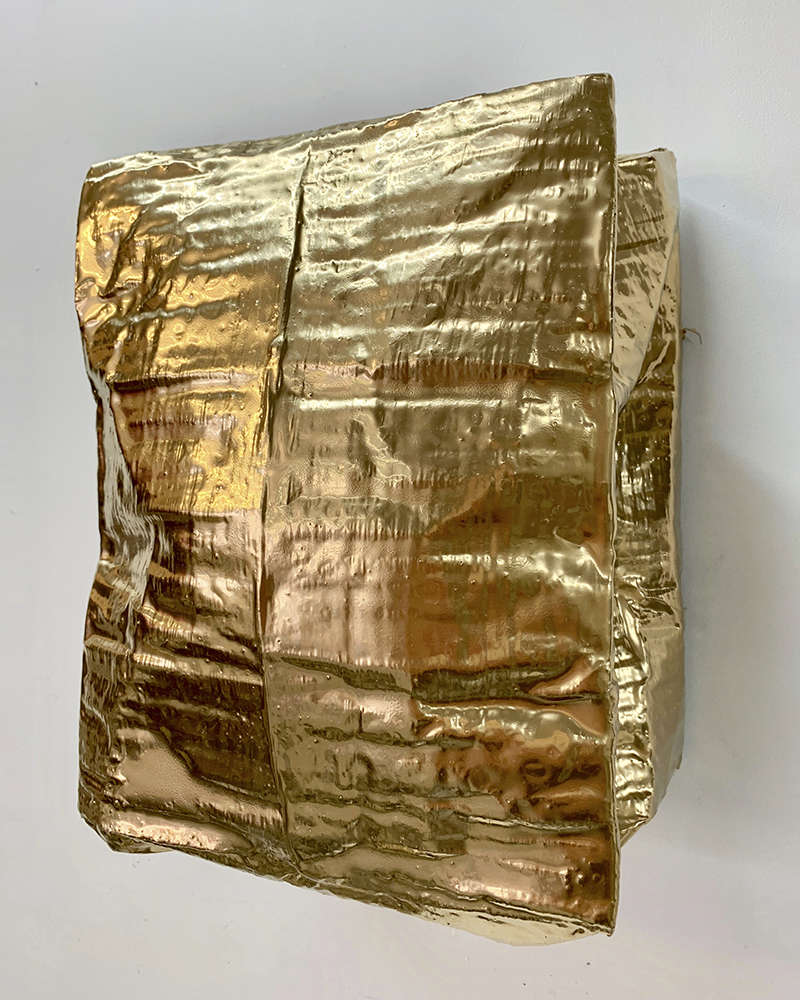

Featured image: Puffery Installation view. 2019.

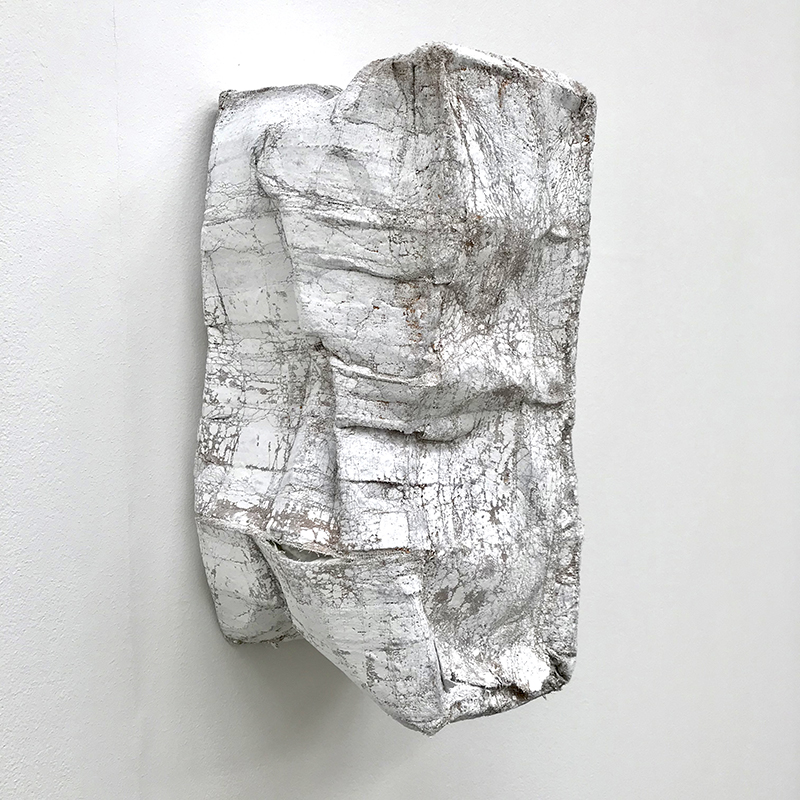

Backbone. 2019.

How did your tryst with art begin?

I have always been creative and a maker of things. My earliest memory is of making a handbag out of a cylindrical cardboard box when I was in kindergarten. Making things was a way for me to make sense of the world, when things around me were chaotic. While the making had no particular direction, it was a constant in my life. This urge for creativity eventually led me to a career in interior design, which taught things like scale, colour, texture, and honed my sense of aesthetics. I also developed paint finishing skills by painting furniture. This in turn led to an interest in painting itself, as I began to paint on canvas.

After a while I began to submit my work to various art galleries and started selling my work. I did this for around six years. Then, I got to a point where I thought that I could either carry on doing this, which was fine, or get a higher art education. I chose the latter. My studies began with a foundation year at Whitecliffe College of Arts and Design in Auckland. During the course of the year the faculty invited me to do an MFA, which I began the following year. It has been one of the most difficult things I have ever done, but at the same time it has been one of the most rewarding things.

After graduation I was approached by The Vivian Gallery in New Zealand, who represent my work. I have been fortunate to have my work included in numerous international shows over the past few years. I’m also represented by a gallery in Melbourne, Australia, called West End Art Space.

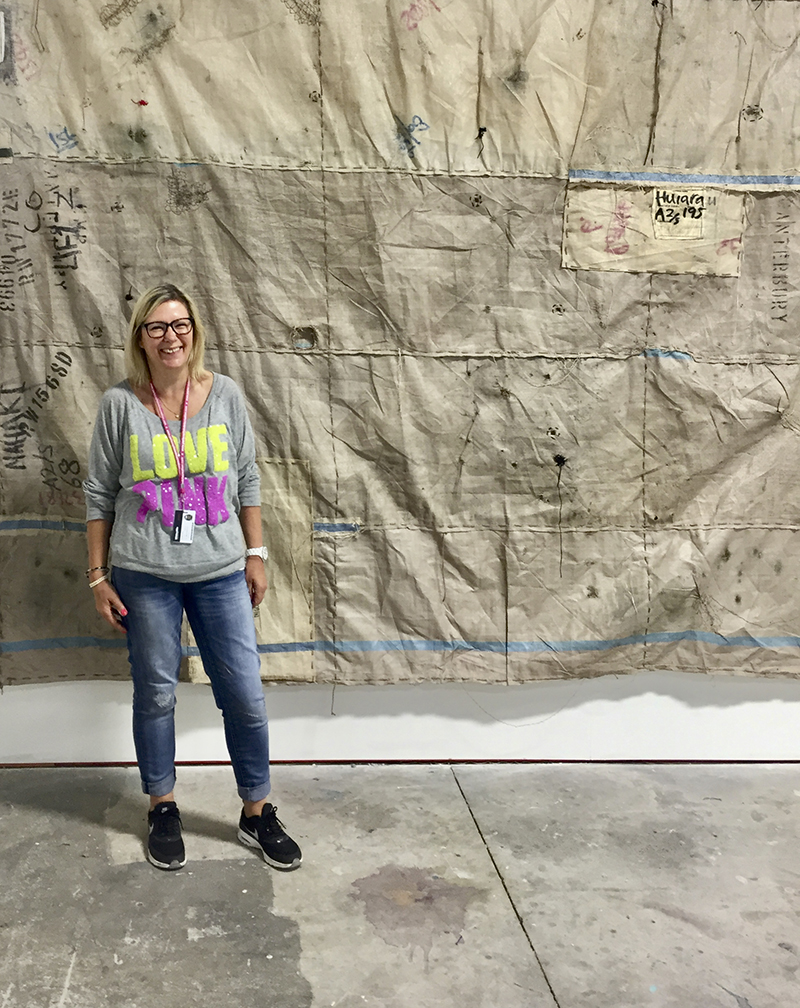

Monique Lacey. 2015. Sack Work.

What is the primary role of an artist? How do you describe yourself in the context of challenging people’s perspectives via your work and art?

For me it is to make things that don’t exist, and to make work that speaks to an issue that I, and hopefully other people, are interested in or find engaging in some form.

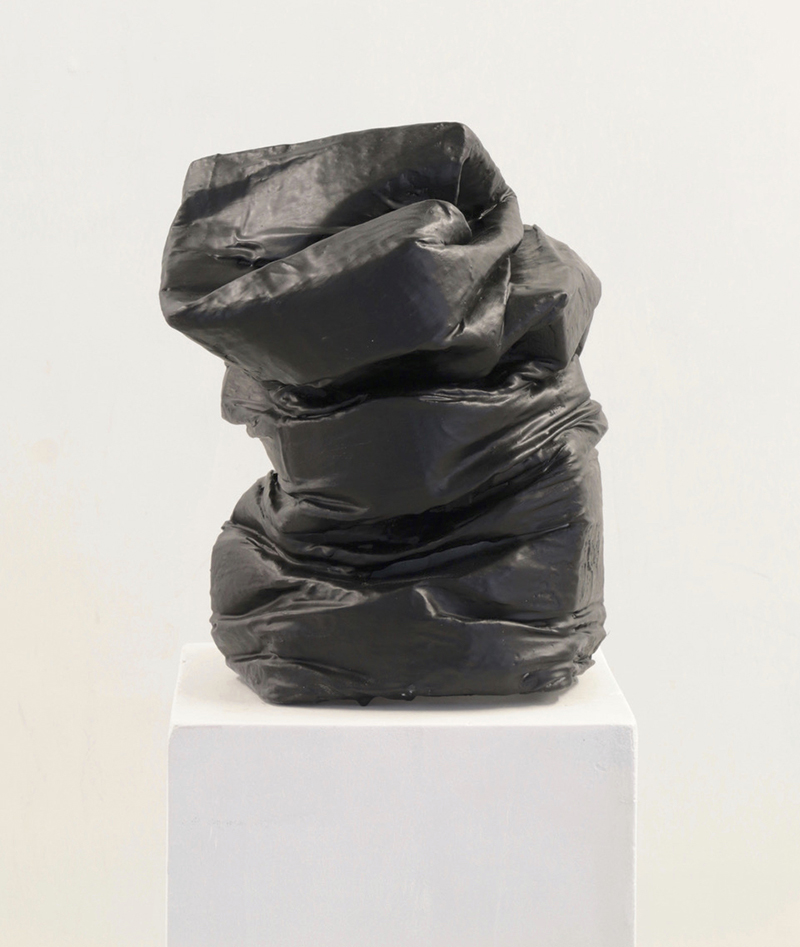

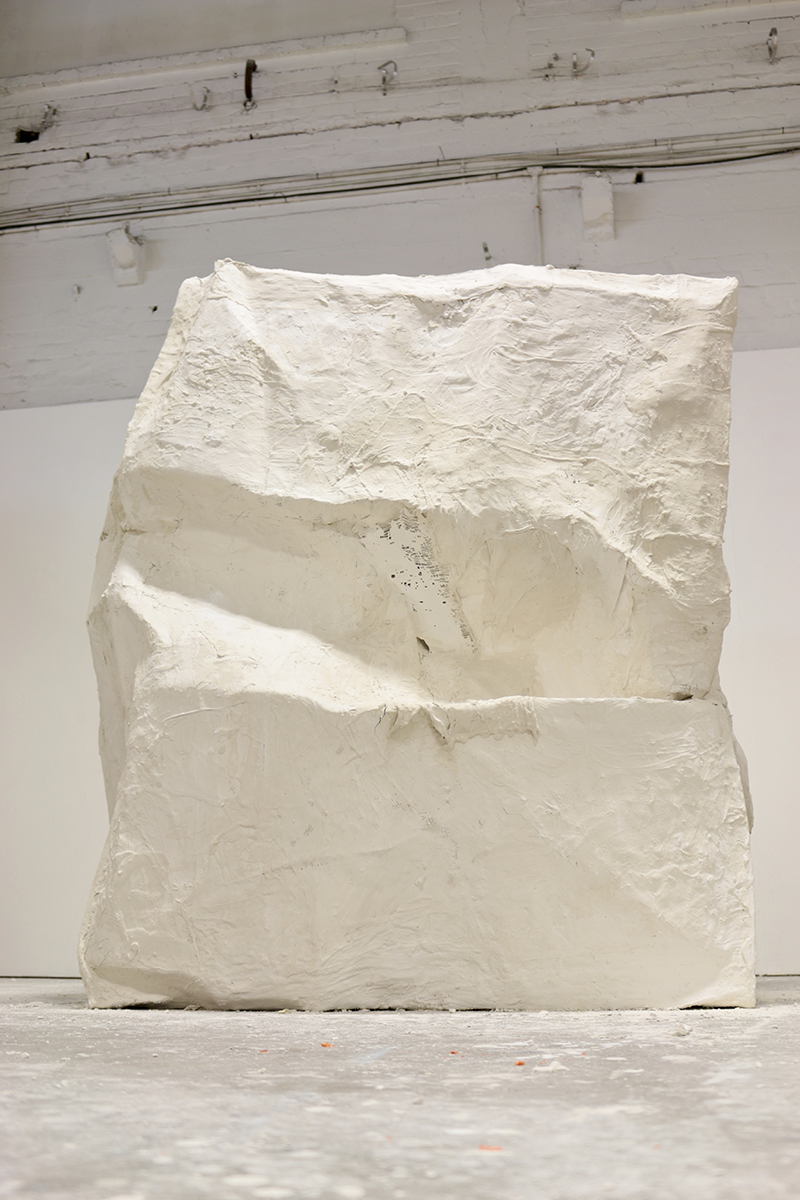

Thinking about my own practice in this context, my work finds its footing in Minimalism, a period in art dominated by male-centric narratives. I am trying to rethink that period through my work and to give my feminine perspective on it. Where Minimalism speaks to surfaces seemingly without craft, my works are made with my own labour and action. And rather than the hard edged lines found in Minimalism, my works are crushed and crumpled. I am taking the Minimalist box and literally crushing it. So, instead of the hard edges found in Minimalism the work now appears crushed, somewhat comical, as well as perhaps feminine. The works function as a commentary on that male-centric narrative that now seems outdated and no longer pertinent.

If Cat Woman’s Costume Was Made Out Of Lycra. 2019.

Let’s talk about the evolution of your practice over the years. Tell us about your commitment to your current medium.

Beginning as an abstract painter, I was particularly interested in surfaces, using materials such as plaster, wax, scrim, paper, bitumen and paint in order to make the paintings. During my university course I began looking at different materials that I could use for making work, becoming more interested in found objects in the process. This progression to working with cardboard and plaster is materially driven, as was my painting practice. While doing my MFA and researching various materials, my interest began to shift towards “sculptural paintings” and wall objects. The question was what material I can use that I can manipulate myself to create these wall objects. In my previous life, before art, I had a retail business.

Everything that was delivered to the business was packaged in cardboard boxes, which when emptied had to be collapsed for disposal. This familiarity and a connection with cardboard led to a natural progression where I started using this material. Gradually the process was refined as I manipulated the material, and after a while I developed processes that allowed me to work with the material to get to the desired outcome. Since then cardboard has been my preferred and primary medium. I don’t feel I have exhausted the possibilities of this medium as yet. I am working with other mediums in my practice although they have a supporting role for now.

Murkey Waters. 2019.

What inspires you?

Materiality inspires me. Surfaces that are weathered, form, texture and scale. I go about my day looking at what is around me, taking photos on my iPhone. If I am stuck and in need of some inspiration, I go to the nearest hardware store. I love walking up and down the aisles looking at things that I may not even recognise, so the items on the shelves become purely material with potential. This encourages my thinking about what I could make with whatever I’m seeing, which then has me considering the things I am in the process of making, in a fresh way.

I work with other mediums and make things that never see the light of day. I recently finished my Book of Procrastination, which was my way of postponing making work for an exhibition. It is an artist’s journal full of paintings and collages that eventually fed into my most recent body of works. I dabble in ceramics, but again it is purely a studio practice with no expectation.

Take us through your process and continuous frameworks of reference.

I listen to other artists talk about their work and I find this really inspiring and motivating, and I also read art books. Interior design-related material continues to be an inspiration. I have been brooding on two quotes for some time now. One is by British artist Phyllida Barlow who suggests that “the bronze with its hollow black space in the middle which we never see, means that the surface is actually more akin to painting than sculpture”. I find this idea intriguing which leads to questions about the boundary between painting and sculpture.

The other quote by Anish Kapoor suggests that “the skin of an object is what defines it. Its weight and mass are contingent on its skin”. This leads me to the question that if the properties of skin and volume are highlighted and emphasised in the work, does it firmly retain its status as painting?

Smoke and Mirrors.

Let’s talk about your career, or if you prefer artistic journey. What were your biggest lessons and hiccups along the way? Which is the most memorable moment?

The most important bit of advice I have ever been given was to “make more work”. I am fairly prolific in my practice, but that advice spurred me on to make even more. I also made a decision to assign zero value to any of the work I make in the studio. These two simple rules allow maximum freedom during the making process. It doesn’t matter if something doesn’t work out because there are always more works in progress that have potential. This also allows me to edit work as there is constantly other work present for comparison.

It’s just like trying to push sh*t uphill.

How do you balance art and life?

As a full time artist I am in the studio much of the time during the week. With my materially driven practice I find myself considering and thinking about art subconsciously. I reflect on what I see, and the ideas percolate through the work I make. I think being an artist is more a state of being, so when I’m not in the studio I don’t stop being an artist. You see the world through an artistic lens, which of course might mean different things for different artists.

How do you deal with the conceptual difficulty and uncertainty of creating work?

Working around a concept allows for clarity in the work. The issue more often than not is that it is hard to define what the concept is in the first place. Doing an MFA clarifies the conceptual side of the practice. Once you know where your practice is at conceptually, then the work you make starts to communicate those ideas. Even when I get lost at times with what I’m doing I try and bring it back to the essence of my practice, conceptually.

Trying to contain the middle aged spread. 2019.

How does your audience interact and react to your work?

I think there is a level of intrigue, as I don’t work in a traditional way with traditional materials. My work can be interpreted as playful and I think people relate to that. I try to focus on giving the work interesting titles, which at times take a lot longer to arrive at then it sometimes takes to make the work. Titles such as If Cat Woman’s costume was made out of Lycra, The elephant in the room and Trying to contain the middle aged spread bring an extra narrative layer to the work. The work is often tactile as I focus on surfaces in my work, and people seem to enjoy that aspect. They regularly ask if they can touch the work.

Sugar Lump.

What are you looking for when you look at other artists’ work? Who are your maestros?

I want to be engaged when I look at art. There is nothing worse than walking past an artwork and thinking “meh”. I want to feel something; the work has to hold me. I look at art from the perspective of being a maker, so I’m looking for the process of the making to be present in the work, but not in a way that seems so obvious as to how it got there. I am a great admirer of Anish Kapoor’s extraordinary pigment and wax works. Currently, I am obsessed with Nick Cave’s work. I love the craft he displays in his practice. His Soundsuits are absolutely exquisite pieces of work. Leonardo Drew is also a favourite artist. I love the scale of his work and his dedication to a specific material. I find Patricia Piccininni’s work absolutely intriguing.

While her work can be quite confrontational on first encounter, you find yourself becoming more empathetic towards the work as time goes on. I saw her show in Brisbane, Australia, last year where she had taken over the entire floor in the museum. It was absolutely mind blowing. I am also a great fan of the Abstract Expressionist period in general. Yves Klein’s blue pigment and gold leaf work, which I saw in the Menil Collection in Houston earlier this year, came pretty close to perfection for me. And then there are Richard Serra, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Sean Scully, Gerhard Richter, Pierre Soulages, Robert Rauschenberg, El Anatsui, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Ursula von Rydingsvard, Phyllida Barlow, Willem De Kooning… the list is endless.

You have spent time amongst artists in flow. What have you observed?

I believe that the one thing that artists in flow have in common is that their output is extremely productive. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they produce art all the time, but they are in the studio thinking about art, making things that might never see the light of day, allowing themselves to fail in order to get to the work that is yet to be made. I think that as long as you work consistently, flow will follow.

Munted.

What is that one thing you wished people would ask you but never do?

It’s not so much the thing people never ask, but more the notion that they assume that it must be a lot of fun to create the type of work I make. I’m not saying it never is, it certainly has those moments, but it is no more fun than say painting a painting or making any other type of art. My practice has a “high risk” element to it as far as the making is concerned, in the sense that I have to make 90% of the work in question, only then to watch it fail when I crush the work. This can be frustrating at times. I realise it is a situation of my own making, but it can be quite trying.

How does your interaction with a curator, gallery or client evolve? How do you feel about commissions?

I have been fortunate to work with great galleries who have put an enormous amount of trust in me. The director of my gallery visits my studio visit on a regular basis to see what I’m making, and gives feedback on the work. Having that input and support is invaluable. On the whole I am free to get on with whatever it is that I’m making and the work generally finds it way somewhere in a gallery.

As far as commissions go, I find them tricky to do as generally it is a request for something similar to an older work. Mostly I would have moved on from that, so it’s not that easy to go back to recreate a particular work. By trying to remake a previous work you lose the spontaneity that made the work successful in the first place.

I was trying to do a runner. 2019.

What are you working on now? What’s coming next season?

I am currently working on a solo show that I have coming up at The Vivian Gallery in Matakana, New Zealand. I am also participating in the Image Object exhibition, which is part of the Mona Foma Festival in Tasmania, Australia. And I also have an exhibition coming up at West End Art Space in Melbourne, Australia, as well as the Spring Art Fair, which is also in Melbourne.

Later in the year I will be heading off to Houston, United States, for an exhibition and residency. I’m also taking part in a group show in Miami in 2020.

Before you go – you might like to browse our Artist Interviews. Interviews of artists and outliers on how to be an artist. Contemporary artists on the source of their creative inspiration.

Add Comment