Contemporary artist Tom Holmes muses about the hundred-and-one roles an artist plays over the course of a life, in an interview with Sonalee Tomar.

Increasingly, I have come to believe that the artist might have a moral obligation to bring us into acceptance of the impermanent nature of the world. That is to say, to bring the viewer closer to acceptance of things as they are, not as one wishes them to be.

How did your tryst with art begin?

The beginnings of my story aren’t particularly happy. I find myself often experiencing a kind of aversion to this question about my background. Suffice it to say I grew up quite isolated in a working-class evangelical home, rural West Texas, a ranch called High Lonesome.

From a remarkably young age I had a clear idea that I’d be an artist. I can’t imagine what I thought that might have meant. I had certainly never seen art in person nor met an artist. The first modern art I saw in the flesh was Donald Judd’s Chinati in Marfa, Texas. A desolate minimalist’s wet dream, variations on a cube tossed across the desert landscape, marched into huge hangers once used for WWII prisoners of war. I would have been a teenager when I saw it, shortly after his death in 1994, maybe. I’m surprised now with what little knowledge I had of art history, that I could intuit the work for what it was, a fanciful monolithic neurotic malignant vision.

This is what art will be after the bomb has scoured cultural meaning from objects, left dry as bones in a dystopian space where metaphor no longer functions. Jesus! I roll my eyes now at the unchecked ego, but I still take the work quite seriously. And, it’s very much a primary impression. I still think of myself as a sculptor in a very similar way. Even though I’m currently making paintings, I think like a sculptor.

I went on to study art, first at the University of Texas in Austin, with Peter Saul and Linda Montano, then UCLA. At the time, it had a big ol’ powerhouse faculty comprising John Baldessari, Mary Kelly, Chris Burden, and Paul Mccarthy.

I might have really come into my own as an artist a few years after grad school when I worked briefly for the post-minimal artist Richard Tuttle. Still remember riding the train with him in NYC, both of us holding on to the steel pole, and him saying, “They (meaning Judd and his disciples, perhaps) wanted to combine form with form. We (meaning he, Bruce Nauman and perhaps a few other contemporaries) wanted to combine form with death.” I can’t be certain what he meant. He often spoke in riddles, but I still think about the phrase often. One might describe my work as the form of grief.

What is the primary role of an artist?

Well, it’s a pretty sticky question as I don’t want to limit the possibilities. There are surely one-hundred-and-one roles the artist plays over the course of a life. Increasingly, I have come to believe that the artist might have a moral obligation to bring us into acceptance of the impermanent nature of the world. That is to say, to bring the viewer closer to acceptance of things as they are, not as one wishes them to be. In the western tradition it’s an especially difficult mission as we tend to roll from one distraction to the next, resisting somehow the discomfort of fully inhabiting the raw, unadorned moment of now.

Art, at its most potent, has the ability to unearth that space – the space to face our mortality, squarely. I have stood in front of a baroque masterwork and felt the weakening of my knees, and time stretched. It’s so rare an experience as to be an anomaly, but I have had experiences with art that do bring me into a kind of alignment with the inevitable choicelessness, observant, electric, and with a faint cool breeze of gratitude. Love made public. As I’ve known it, experientially, I’m certain art has that capacity. Oh, I know that sounds terribly earnest. One imagines that humour is potentially equally transcendent.

How do you describe yourself in the context of challenging people’s perspectives via your work and art?

Now, I am a little less certain of the agency an artist has in revealing mystic truths. It may be that the artist has far less agency in what moves through the work than we are taught to believe. What so often happens in the academy is an enforced artificial equitability that privileges the conceptual model. A student should, conceptually, be able to research their way to good art, construct cognitively artistic competence. The aim might be socially admirable, but having been in the art game this long I’m led to believe that’s so much theoretical rhetoric, devoid of substantive artistry. The hard truth is artists are not trained. If one is graced and burdened by this vocation the best work seems to arrive just outside one’s agency, and yet, the studio still demands quest, daring, and growth.

What were your biggest lessons and hurdles along the way? Which is the most memorable moment?

I stayed in Los Angeles a few years after grad school then moved to NYC, in 2005 I think. The struggles of NYC made me a better artist and I was able to establish gallery support that still sustains me. However, by the end of my time there I was done with the city and the city seemed to be done with me. A perfect storm of hardships and challenges came close to breaking my spirit. And, it dawned on me, in one of those rare moments of epiphany, “Oh, I could be broke anywhere!” I made a quick decision to leave the city and move onto a Radical Faeries commune in rural Tennessee, isolated and deep in the backwoods.

That decision to leave the cultural centre for the middle-of-nowhere really has defined my life, in a way, for the last decade. I chose the nature experience over the urban experience and I can say it has benefitted me, and the work, in subtle, but definitive ways. A city is really no more than whom you are in love with and how much you pay in rent. And, if you’re not in love, well surely you’re paying too much in rent.

What inspires you? Take us through your process and continuous frameworks of reference.

I’m tickled by the truth of the phrase “inspiration is for amateurs”. Having been at this art game for this long it really seems more about showing up and diligently doing the work balanced with released expectations – doing one’s duty without grumbling. Who knows where the ideas come from, but they are more likely to strike if your hands are busy. Good ideas land in dirty hands. Well, perhaps I should clarify that. I mean to say one might bring awareness to all aspects, all activities of life, of work. I have gained countless hours, counter-intuitively, by meditating silently. My meditation teacher, the late S.N. Goenka, would encourage one to sit with the awareness of every changing bodily sensation so that one might continue the practice in daily life, being constantly aware.

It seems holding, sometimes contradictory ideas in one’s head at the same time, can lead to a path into the work. It seems I’m advocating for a contemplation of one’s death as a method of living with a keener sense of life. I’m attempting very abstract ideas about civic grief in traditional oil painting. I’m demanding of the viewer the recognition that the most humble life is noble.

How do you deal with the conceptual difficulty and uncertainty of creating work?

It may be that the entire practice is one of uncertainty – taking some solace, if not pleasure, in one’s confusion. Beats me, though.

I’m the student of almost every major first generation conceptual artist working in the early ’70s and I’ve sadly come to the conclusion that generationally their version of artistic integrity is inferior to the generation of abstract artists that preceded them. Now, those are fighting words and deserve more explanation than I have room for here. But, one measure of artistic failure might be if a work is better accomplished by the verbal. That is to say, if a work is dependent on language it surely may fail in the broad visual field. In the same breath, I’ll say I’m indebted to many innovations of conceptual art: appropriation, political content, archivally inappropriate materials, and identity concerns being just a few.

If minimalism reduced abstraction to its logical end, conceptual art aspired to compete by squarely putting an end to the vagaries of abstract expressionism. The trouble comes when its practitioners, though a more diverse bunch, do little more than continue the stranglehold that straight white dudes have had on reason and rationality for goddamn 250 years!

To work abstractly, either with abstract concepts or non-objective compositions, is to leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach. I have to trust the fact that my eye is wiser than I.

Tell us about the evolution of your practice over the years.

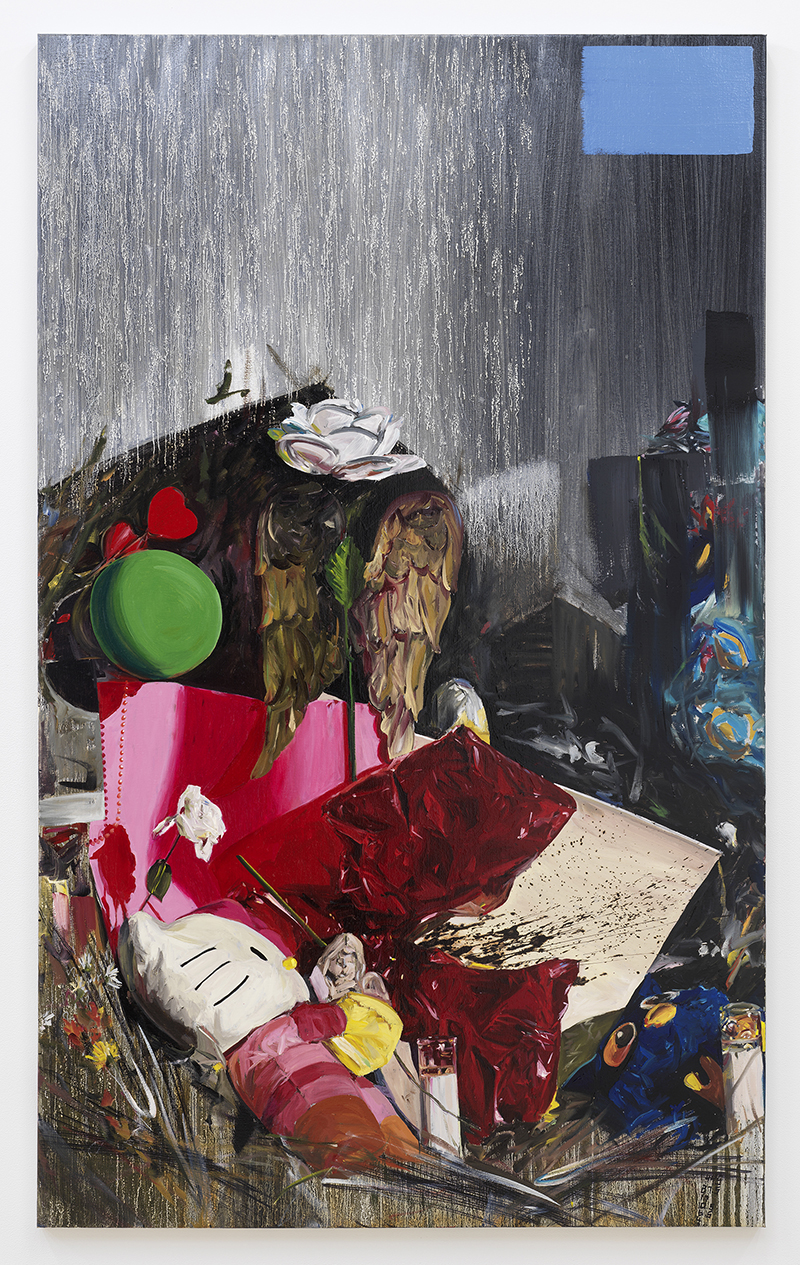

Big question. It’s like trying to catch up with a friend you haven’t seen in 20 years. As much as I’d love to be a painter of monochromes, I just ain’t one thing. The work really isn’t one thing. As mentioned earlier, I have, for the last year or so, been making realist oil paintings from images of temporary memorials at the sites of gun violence. Nobody is more surprised than I that I’m painting, and I am pretty good at it haha... It’s certainly not where I began. As a student my way into art was via performance. In part, because I was an attention-starved church-damaged queen. And in part, because the brightest member of the faculty was video and performance artist Linda Montano. I had such a vehement disdain for the commercial aspect of painting, naive as it was.

Via performative video and photos there was always an interest in the metaphoric, in a way Duchampian, relationship to objects and the sculptural arrangement of objects. As I was a grad student during the godawful Bush years, a great deal of the work focussed on the absence of the performer – detritus after political protests, memorials in the wake of 9/11, roadside memorials and the like.

Fast-forward to my first solo show in NYC, 2010.

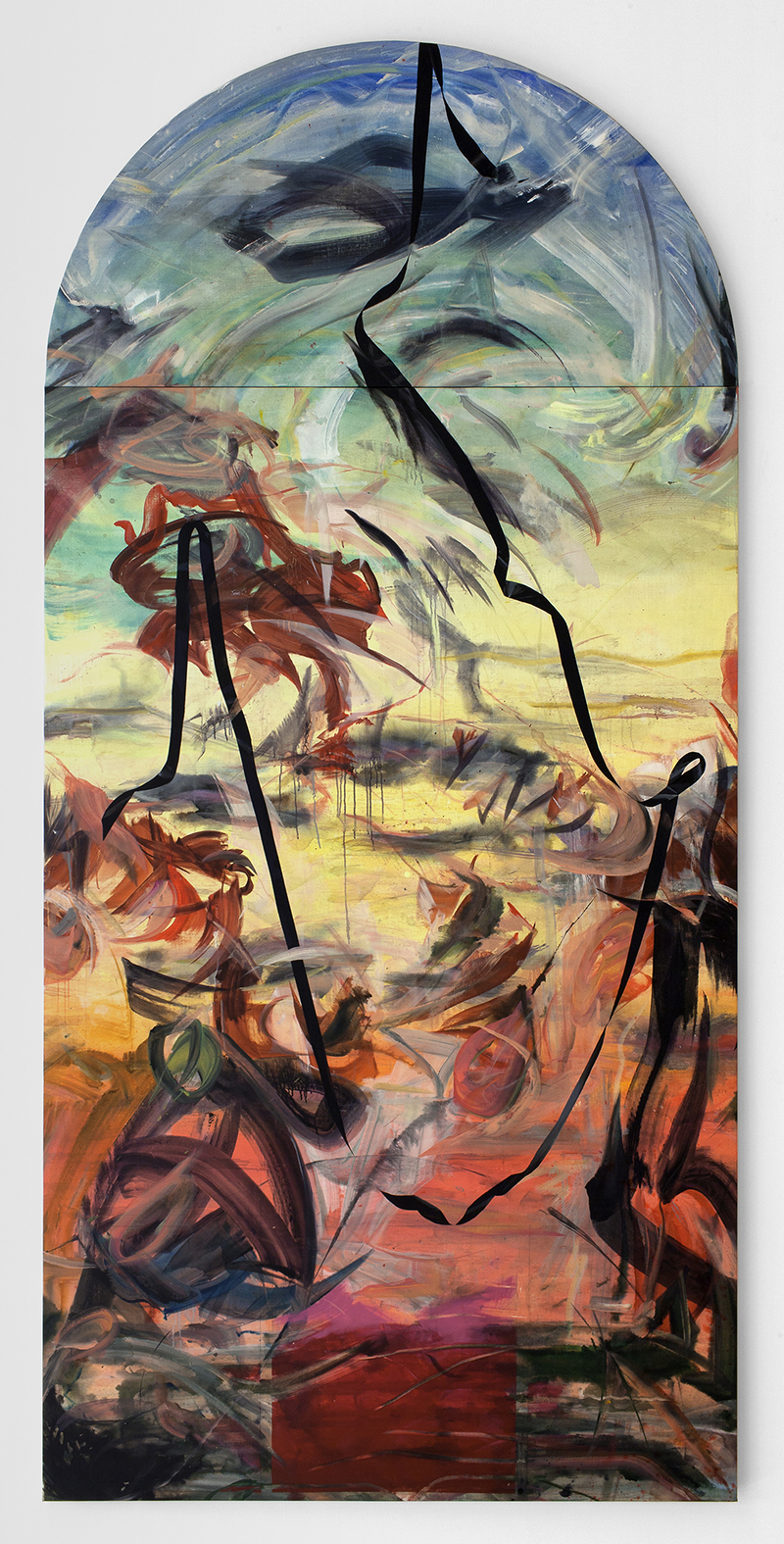

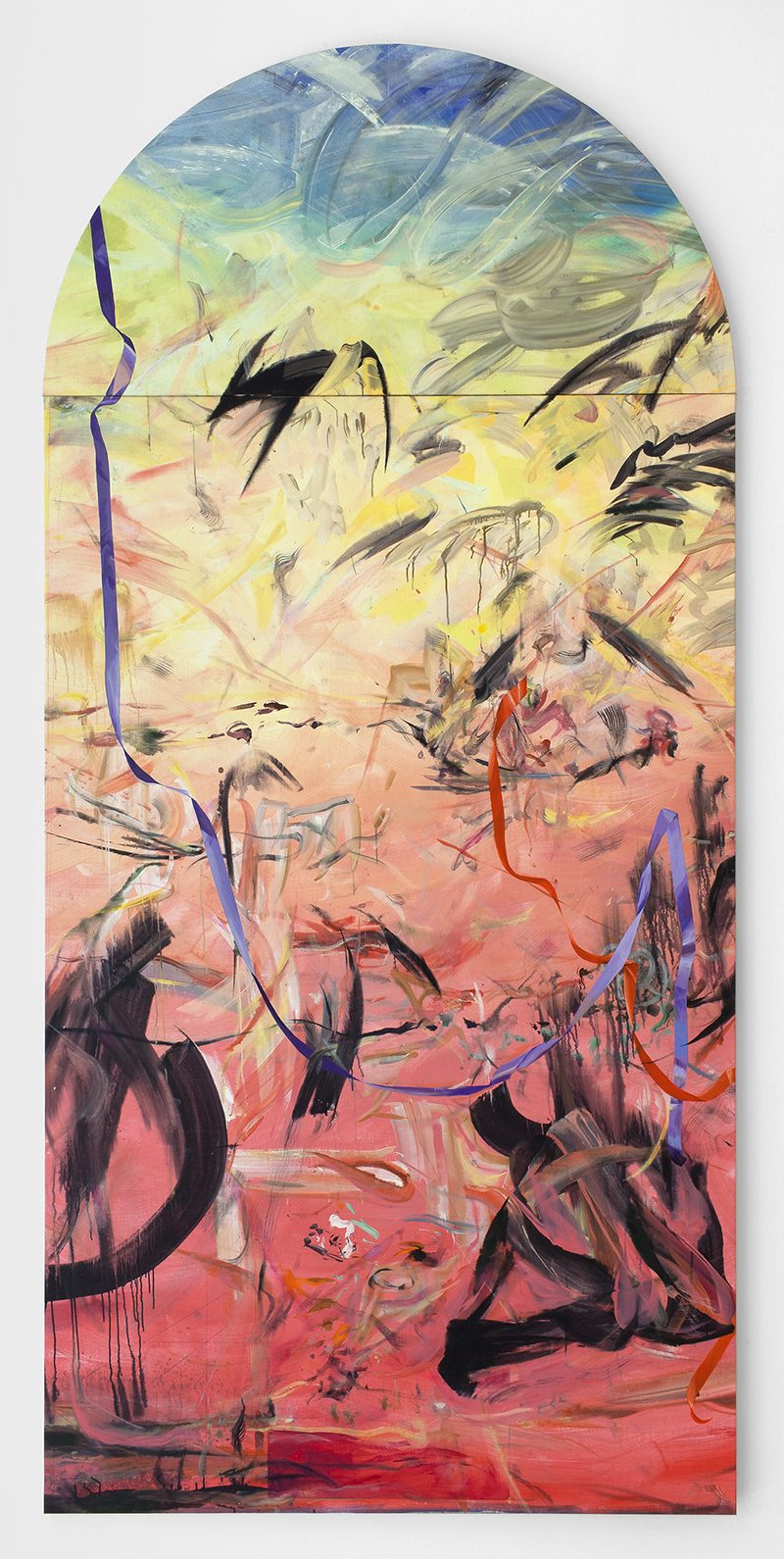

The show was made up of two sculptures. One, a stack of cinder blocks painted shades of yellow, I deemed a gravestone. And two, a Trix® cereal box filled with cremated human remains, bound with wire. Carrying forward themes of the funerary and pop metaphors I produced several gallery shows and a solo museum show with works made up of the most modest of materials. A distinct break in the work comes around 2014 when, via meditation and an interest in hypnosis, I begin a kind of large scale automatic drawing practice, often atop the pop graphics I had used previously.

There was a very real appetite to engage with an abstract practice, one that really unearthed the subconscious. I had lost everything in a fire that destroyed my home and studio and had left me badly burned. I think the work made in the aftermath of that trauma sought a far less cool relationship with images and their meaning.

How do you balance art and life?

So often they are inextricable for me. I will say though, if one finds oneself in a transitional place in life it is

very useful to make lucid distinctions between what the work needs and what you need. Inevitably one will be privileged and there will be sacrifice, but making the distinctions can help parse out choices. I’m in a place of great privilege, as I’m not a family man. My sacrifices are my own.

How does your audience interact and react to your work?

I honestly don’t have a clue. At times I feel so isolated from an interested audience that the solitude is near unbearable. A studio practice, cave painting, is a very lonesome business.

What are you looking for when you look at other artists’ work?

These are trying times. Our political situation, over here, is bananas. This may all look innocent if followed by more trying times. But, what seems noteworthy is how little I see artists responding to this moment. Most are tone deaf.

The scene, at least in NYC, is just abysmal at the moment. On my last trip into the city I saw the Whitney Biennial and was left feeling so uninformed, just numbed by all the choices made out of fear. I’m holding out hope that the coming artists of Gen Z won’t be as humourless and self- righteous as millennials. More than any other fault, the sheer cowardice of stylistic monotony and millennial branding leaves me so empty. As the market drives young careers it looks increasingly as if we’re living in the last half of the ’80s, which can just get snipped out of art history, as far as I’m concerned.

Oh that did sound bitter, forgive me. I think of heroes often. And, it’s always interesting to see whose work you outgrow or alternatively grow into. As a younger artist I knew Cady Noland to be God – insomuch as nobody had heard from her in a long while. I still look closely at the work of David Hammonds and Richard Tuttle.

Which shows, performances and experiences have shaped your own creative process? Who are your maestros

Rachel Harrison has been uniquely kind to me. The voices of my teachers and classmates, of course, still sound off in my head, projections to which to aspire. A few artists I return to when lost are Joan Mitchell, Cy Twombly, Howard Hodgkin – models for liberation in the artistic practice. A few, bit more obscure, characters inform me from time to time like George Inness, Pat Passlof, James Suzuki, Fritz Scholder… Oh I could go on and on.

More than anything I’m informed by baroque painting. The confidence in Frans Hals’ brush is exhilarating. The gravity, or lack thereof, in Giovanni Battista Tiepolo will put you flat on your back. It’s not often that I have much interest in figuration or allegory. Mostly it’s just the dazzling ability to compose a picture that includes so much, so much space. Masters of composition, the best ones create space – space nobody even knew existed before.

You have spent time amongst artists in flow. What have you observed?

Working and creating while in the zone is so rare and inexplicable, as to denigrate the state of grace with our crudest of tools – words. I wish it for us all. I’m reluctant to say this, but there can be a rather curious characteristic to being in the zone. As if that small still voice can only be heard in contrast to cacophony.

What is that one thing you wished people would ask you but never do?

Aw, I like the question, but don’t seem to have an answer. In truth, perhaps one gets the audience, the curiosity, one deserves eventually. I have to believe my work is more articulate than my chatter.

How does your interaction with a curator or gallery evolve?

I have what many artists don’t – an honest and very smart dealer. The business relationship with my gallerist, which grew out of friendship, has been so much more important to me. It’s the kind of complex relationship they just don’t teach you about in school. I’m not sure where I would, perhaps, like to be in my career, but I’ve gotten what opportunities I have in large part to my association with Bureau in NYC. I’m especially grateful to be able to maintain my practice outside the city, something most dealers wouldn’t support.

I have far less affection for hemmed-in curators, I’m afraid. They really are the one-night-stands of the art world. Rarely is an artist afforded sustained support from a curator, lucky if you can get through a show without strangling one another.

What are you working on now? What’s coming next season?

I’m grateful to have just completed a solo gallery show in NYC and have a little down time to regroup, solidify ideas and begin on the next cycle of work. I’ll be travelling soon to London, Paris, Prague, and Vienna hoping to see some baroque bits of wonder. I want to be be present in the sublime. I’m happily taking suggestions.

Before you go – you might like to browse our Artist Interviews. Interviews of artists and outliers on how to be an artist. Contemporary artists on the source of their creative inspiration.

Add Comment